They called 911 to help their mentally ill son. A Minnesota county never sent crisis responders.

When Brent Alsleben stopped answering his mother’s calls and texts in the fall of 2022, she called 911.

She feared her eldest son, who struggled with mental illness, had hurt himself. He lived alone in an apartment in New Auburn, a small town about 65 miles west of the Twin Cities.

Tara Sykes told Sibley County dispatchers the 34-year-old had bipolar schizoaffective disorder. He had a history of burning himself and had been hospitalized twice before. Days before, he’d missed a doctor’s appointment.

“I feel like I couldn’t have done any more,” she said. “I told them everything.”

Dispatch reports obtained by 5 INVESTIGATES and corroborated by multiple interviews show Sykes and other family members called 911 eight times from September to December.

Each time, Sibley County sent sheriff’s deputies to check on Alsleben, but advised the family there was little they could do to help.

Sykes later learned that wasn’t true.

A year earlier, Minnesota lawmakers passed Travis’ Law, which requires 911 dispatchers to “include a referral to mental health crisis teams, where available.”

But a review of incident reports and 911 calls reveals the Sibley County Sheriff’s Office never sent or requested the assistance of mental health responders to help Alsleben.

The sheriff declined an on-camera interview to explain why, but said in a statement that “response to mental health calls has and always will be a priority for this office.”

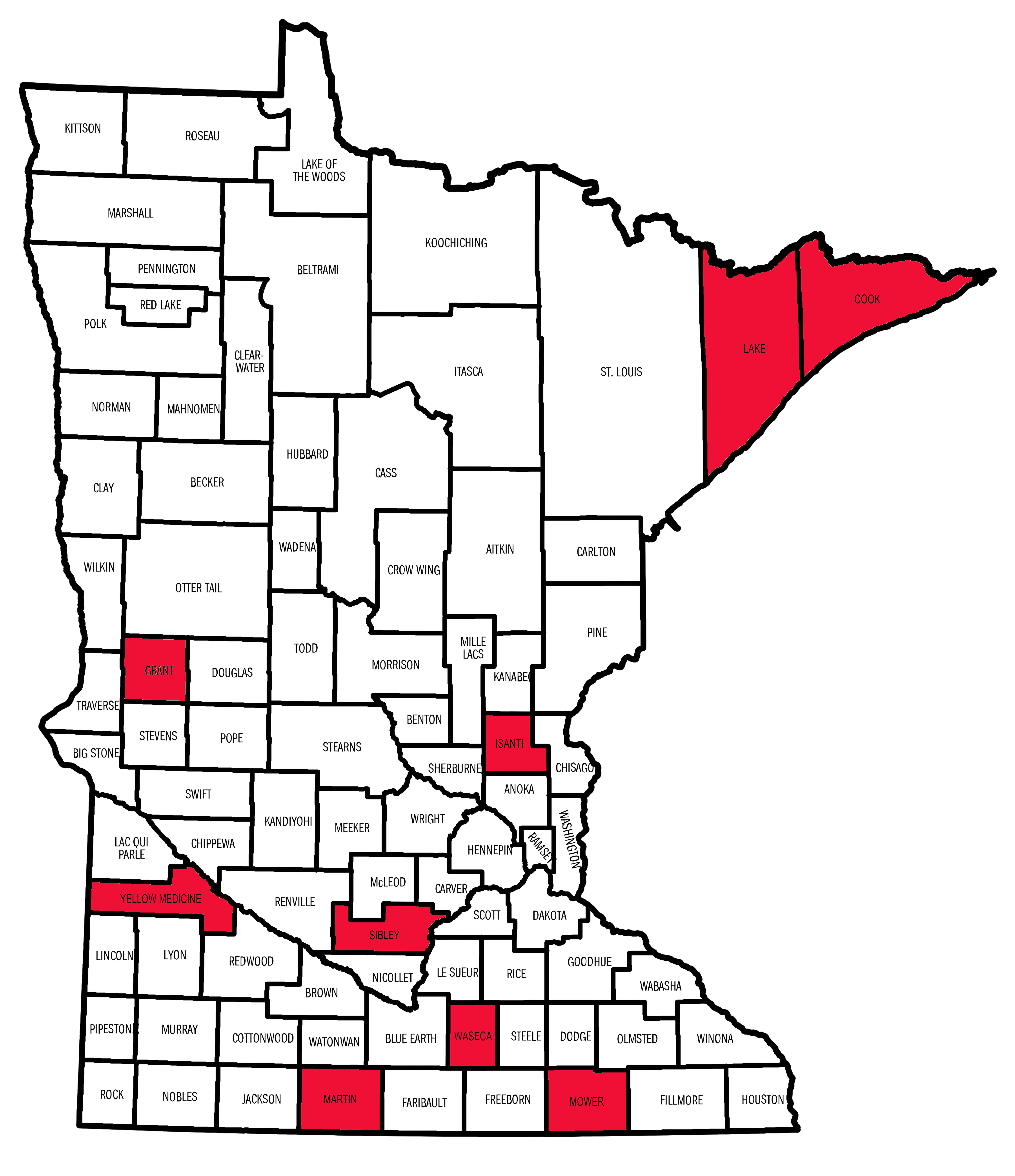

But Sibley County is one of nine counties that didn’t refer a single case to crisis responders in the year and a half after Travis’ Law was passed, according to state data reviewed by 5 INVESTIGATES.

Mental health advocates say the data demonstrates that the law is being inconsistently implemented across the state, often with dire consequences to people in crisis.

Deb LaCroix-Kinniry works with a group that offers training on Travis’ Law.

“There needs to be some level of accountability,” she said in an interview. “It is a law.”

No referrals

Named for a Minneapolis man who was shot and killed by police during a mental health crisis, lawmakers celebrated Travis’ Law as a major step forward in the fight for an alternative response to mental health calls.

Every county has access to mobile mental health crisis teams through a state-sponsored program. The Minnesota Department of Human Services (DHS) collects information from those teams annually to learn where referrals for services come from.

Data from 2021 and 2022, reviewed by 5 INVESTIGATES, list no referrals from law enforcement in nine counties.

Data source: Minnesota Department of Human Services

Some counties argue the data doesn’t illustrate the steps they’ve taken to implement the law. In Cook County, for example, the sheriff’s office developed its own crisis response team through the county’s public health agency.

Other counties blame a lack of resources. Isanti County Sheriff Wayne Seiberlich said the county’s contracted mental health team had no staff available in 2021 and 2022 to respond to referrals from law enforcement.

Lake County Sheriff Nathan Stadler, who took office in 2023, told 5 INVESTIGATES he had no idea this was even a law.

“As far as I can tell, we don’t have a policy for our dispatchers in place, but we will, now that you’ve brought this to our attention,” he said over the phone earlier this month.

No oversight

LaCroix-Kinniry, the mental health advocate, said part of the problem is that no one is overseeing the implementation of the law at the state level.

“We need to have somebody monitoring this and offering help, quite frankly, as a resource to help them get it implemented,” she said.

According to the Minnesota Department of Public Safety (DPS), 911 dispatch centers are operated by a county’s sheriff’s office, independent of the state. A spokesperson confirmed DPS does not provide guidance on Travis’ Law.

“If they’re not doing it, there needs to be some kind of accountability there,” LaCroix-Kinniry said. “If you or I don’t follow a law, there is a consequence for it.”

Sibley County Sheriff Patrick Nienaber declined multiple interview requests over the course of three months.

“We will continue to utilize resources to train and equip our staff to respond appropriately by balancing the safety of the community and potential threats to our deputies,” he wrote in a statement.

5 INVESTIGATES sent specific questions about his office’s policy on dispatching crisis responders to mental health calls. When he wouldn’t answer them, reporter Kirsten Swanson approached him outside of a county board meeting in January.

“I issued a statement, Ms. Swanson, that’s what I’m going to stand with,” Sheriff Nienaber said before walking to his office.

Deadly consequences

As time passed, Alsleben’s family grew increasingly frustrated with law enforcement’s response and concerned for their son’s wellbeing.

In November, Alsleben’s stepfather called 911. The family had finally spoken to their son on the phone. They knew he needed an evaluation and medication.

“He is beyond delusional at this point,” Jay Sykes told the dispatcher. “Now it’s at the point where he’s going to die if he doesn’t get in the hospital.”

But Alsleben never made it to the hospital. In December 2022, the 34-year-old was shot and killed by law enforcement from the Hutchinson Police Department in his apartment after an hours-long standoff. Investigators say Alsleben stabbed an officer with a knife during a struggle with SWAT officers.

The family believes Sibley County’s failure to follow the law in the months leading up to the shooting had deadly consequences.

“We needed somebody in the professional realm to help out,” Jay Sykes said. “I believe that if they would have sent a mental health professional, someone trained to deal with individuals who are disabled and or mentally ill, that Brent could be sitting here talking with us.”

Jay Sykes said talking about what happened to Alsleben is their way of garnering awareness of Travis’ Law. The family is also pushing lawmakers to consider legislation that would bolster alternative responses to mental health calls.