Indian boarding schools apology sparks renewed reconciliation efforts in Minnesota

Gabe Desrosiers describes it as ironic.

The University of Minnesota Morris teacher works to preserve and pass on the very thing that the federal government once sought to eradicate.

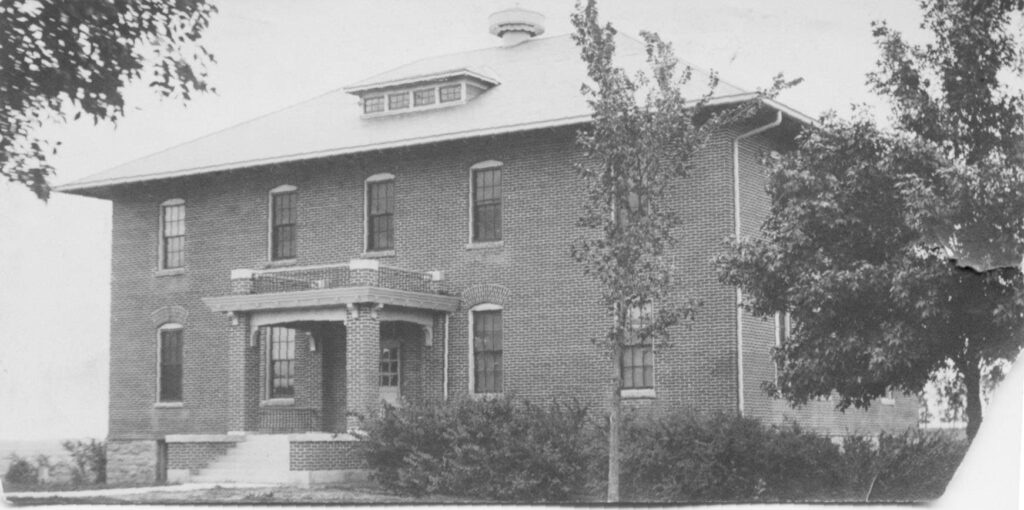

The campus sits on land that was once the Morris Industrial School for Indians, a federally run boarding school that suppressed Indigenous children’s culture in an attempt at forced assimilation.

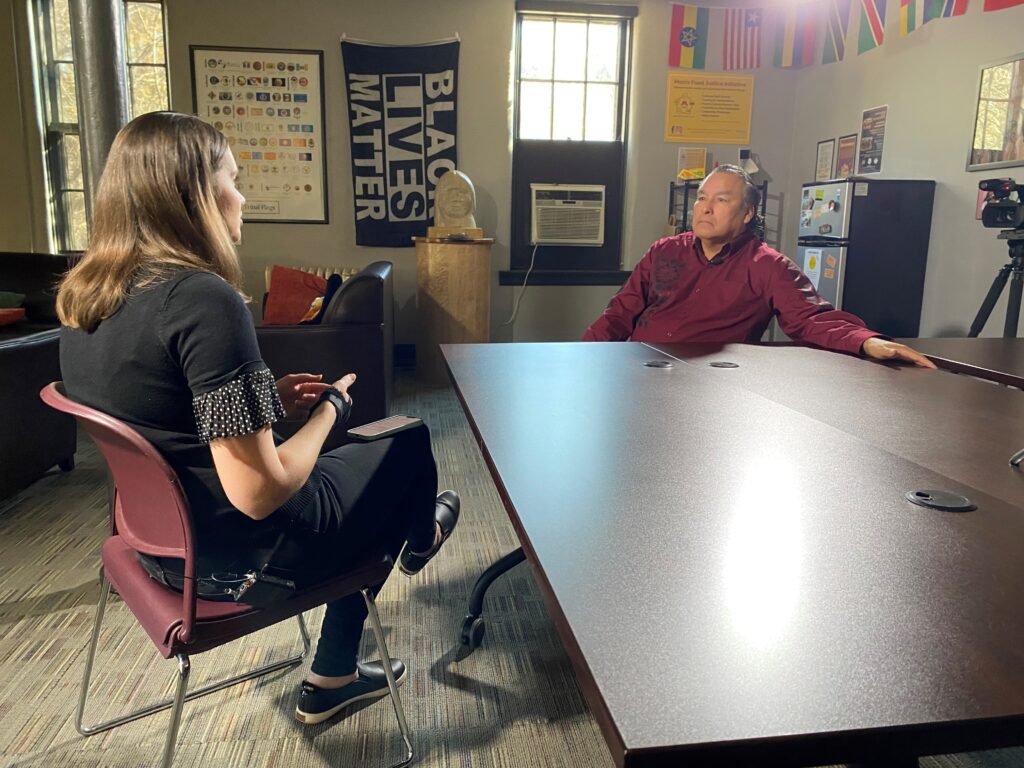

“This was a place once that, you know, forbade Native students to learn about song and dance, to learn about language,” Desrosiers said. “This is what I do here on campus.”

Desrosiers is reminded of that history every day. His office is housed in the last remaining building from the campus’ boarding school era. The two-story brick building served as the boy’s dormitory.

“You can feel the presence of the children that were once here,” he said during a recent interview.

The Morris campus is one of 20 sites in Minnesota identified in a federal investigation released this summer by the U.S. Department of the Interior.

Following the extensive probe, the federal government is making amends for the first time in history.

Late last month, President Joe Biden visited the Gila River Indian Community in Arizona and offered a formal apology to the Native families who have endured generational trauma as a result of the assimilation policies of the time.

“It’s horribly, horribly wrong,” the president remarked. “A sin on our soul.”

As the federal government takes responsibility for the policy of the time, school leaders at U of M Morris are moving ahead in their commitment to researching the school’s past.

For decades, starting in the late 1800s, the government removed Native children from their families and sent them to boarding schools.

Photos from the era show the students with their hair cut off and dressed in uniforms.

In 2021, 5 INVESTIGATES traveled to Pipestone, Minn., the location of another federal Indian boarding school.

Elders in the community recounted memories of the sprawling campus they remember from their youth.

WATCH: Hidden History: Federal investigation generates new interest in Minnesota’s American Indian boarding schools

The federal investigation acknowledged that children endured harsh treatment in these schools and found 973 children died while attending boarding schools.

But U of M Morris Chancellor Janet Ericksen said those findings are incomplete.

“If you talk to anyone in a Native community around here, of course students died in boarding schools,” she said during an interview. “They knew it. They knew their relatives had died at this particular boarding school.”

For nearly three decades, students and professors at the school have researched the boarding school era, attempting to learn more about what happened to the children who were sent here.

Ericksen’s predecessor launched an effort to search the campus and surrounding grounds for any evidence of burial sites or other human remains.

“We don’t have anything definitive to suggest that there are, but that’s why we keep looking,” she said.

Desrosiers said while it was important to hear Biden’s apology, the government must follow it with action.

“Doing that research and uncovering facts are important to begin the process of truth telling,” he said.

The federal investigation lays out multiple recommendations for how to move forward, including investments in programs that support Native Americans and tribes, building a national memorial and identifying and repatriating the remains of children who never made it home.

Next summer, Chancellor Ericksen said the school will partner with a private firm to search the campus using ground penetrating radar.

The decision on what to do with any discoveries, however, will be left to Native people in the community.