Community members gather to reflect on the forced assimilation at American Indian boarding schools

[anvplayer video=”5138500″ station=”998122″]

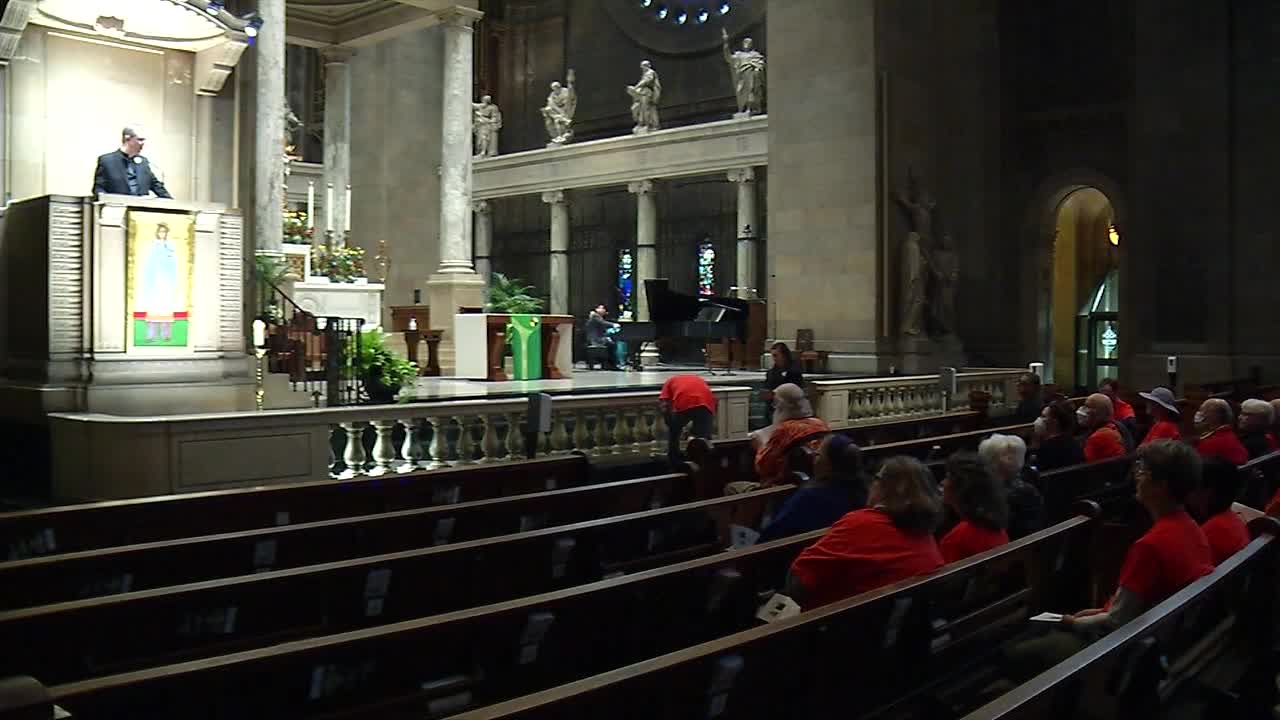

Saturday, people across the Twin Cities came together at the Basilica of St. Mary to remember and reflect on the forced assimilation of American Indians.

Beginning in the late 1800s, the federal government took American Indian children from their families and sent them to boarding schools throughout the United States.

“When these kids were brought there, or taken from their homes… they cut their hair off,” Alice Erickson— of Pipeston, Minnesota — said. “I see a lot of pictures with these little kids all have the same haircut.”

5 EYEWITNESS NEWS first interviewed Erickson back in 2021 when the federal government launched an investigation into American Indian boarding schools.

A two-day event this weekend in the Twin Cities — a sort of extension of Canada's Truth and Reconciliation Day — was created to discuss the Catholic Church's role in the assimilation (KSTP).

That investigation was a direct response to terrifying findings in Canada, where penetrating radar revealed the bodies of hundreds of Indigenous children.

Over 500 Native American boarding school deaths so far, US report finds

The mass graves were discovered at a facility just like the Pipestone Indian School in Minnesota, where Erickson’s grandmother attended years ago.

For almost 50 years, the U.S. government sent American Indian children to these training centers to work and live.

Although those boarding schools have been closed for well over half of a century, the effects linger.

Now community members are working to heal through this generational pain.

A two-day event this weekend in the Twin Cities — a sort of extension of Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Day — was created to discuss the Catholic Church’s role in the assimilation.

Community members have been invited to come together to pray, listen, sing and acknowledge the Indigenous communities affected.

“Healing is going to require some real honest look at what happened, what are all the pieces, so that maybe they can begin to have some closure,” Michele Hakala-Beeksma, a member of the Grand Portage Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, said. “It’s going to take a long time. It maybe never get to complete, you can’t erase the past.”

The U.S. Department of the Interior released its first report on this investigation earlier this year, confirming “the United States directly targeted American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children in the pursuit of a policy of cultural assimilation that coincided with Indian territorial dispossession.”

The report identified at least 53 burial sites for children across the boarding school system and expects to find more sites as the investigation continues.