State of Resignation: How Minnesota ‘cleans the record’ for once-fired employees

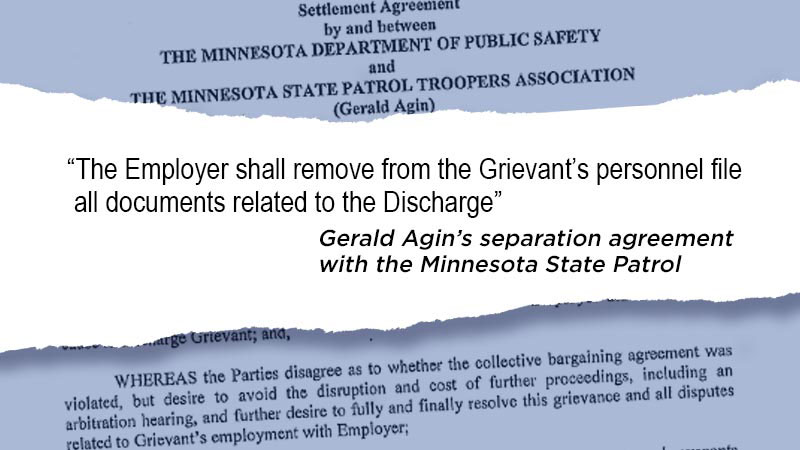

In a fit of rage on the Fourth of July in 2018, police say an intoxicated Minnesota state trooper pinned his wife to the floor, choked her to the point that she struggled to breathe and smashed her phone to keep her from calling for help. After Gerald Agin was charged with two counts of domestic assault, he was ordered to surrender his firearms.

Agin pled guilty to disorderly conduct in January 2019. Less than three months later, he was fired for what the state patrol now calls “horrendous” conduct.

Yet, there is no mention of Agin’s termination or what led to it in his state employment records.

That’s because Agin, whose attorney did not respond to multiple requests for comment, was allowed to resign after his union challenged his firing.

In a statement, chief of the Minnesota State Patrol, Col. Matt Langer said this “guaranteed our objective” of ensuring that “Mr. Agin would never again serve as a trooper.”

As part of a settlement agreement to avoid an arbitration hearing, the state patrol agreed to remove all disciplinary records from Agin’s personnel file—which can be reviewed by the public, media organizations and prospective employers.

[KSTP]

It is part of an emerging legal strategy that a long time labor attorney calls “cleaning the record” and it is quietly taking place behind closed doors at dozens of state agencies.

5 INVESTIGATES found those agencies regularly revoke discipline, remove records and even issue large payouts to once fired employees in exchange for their resignations.

In several cases, state agencies have even deliberately misclassified terminations as lay-offs in an apparent effort to purge any reference to discipline.

Jane Kirtley, a law professor at the University of Minnesota, says it’s a legal strategy adopted from the corporate world and an obvious effort to circumvent the state’s public data laws that are supposed to provide a level of transparency for public employees.

“It’s one thing if you’re dealing with the private sector. Companies can pretty much do anything they want in terms of termination agreements,” Kirtely said. “But here we are talking about the expenditure of government money. We’re talking about government employees and their possible misconduct. Both of those things are matters of great public interest.”

Pattern of payouts

A review of settlement agreements from more than 25 state agencies shows more than 100 employees have resigned since 2013 after initially being fired or informed of their terminations.

More than a third of those employees received payments ranging from $1,000 to $60,000.

In the last eight years, the state has paid out more than $850,000 to once fired employees.

The settlement agreements, which have not been previously disclosed, provide few details as to why those employees were initially terminated.

However, a review of police reports, court records, and other publicly available information show several employees were allowed to resign just weeks after they were accused of serious wrongdoing such as drinking on the job, physical abuse and even sexual misconduct.

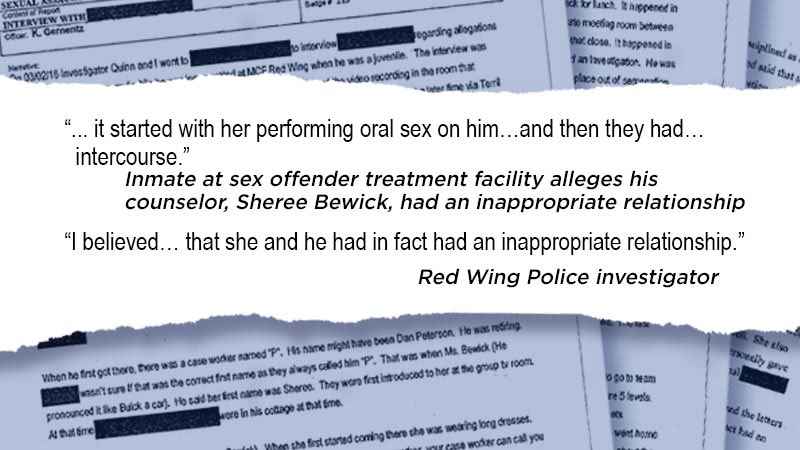

Sheree Bewick, a former counselor for the Department of Corrections (DOC), was initially fired shortly after she was accused of sexually abusing a teenage boy in the state’s sex offender treatment program.

The former inmate told police in early 2016 that Bewick had engaged in sexual acts with him nearly a decade earlier when he was only 15 years old, according to records obtained by 5 INVESTIGATES.

He claimed they had sex multiple times in different rooms inside the correctional facility in Red Wing and that Bewick had “promised to get him out” early.

Multiple attempts to contact Bewick by phone and at her home were unsuccessful. She denied the allegations when questioned by a detective with the Red Wing Police Department.

That detective later wrote in an incident report that he believed Bewick “had in fact had an inappropriate relationship.”

While the county attorney’s office ultimately declined to charge the case, Bewick received a discharge letter from the DOC that June. The following year, though, all records related to that discipline, including any internal investigation or complaints, were removed from her public file after Bewick’s union, MAPE, filed a grievance.

A DOC spokesperson did not answer questions regarding the allegations against Bewick, her initial firing or her settlement.

“The grievance process can lead to unpredictable outcomes,” Nicholas Kimball said in a statement. “So, at times, we use our authority to settle a grievance to mitigate the potential costs and uncertainty.”

In exchange for her resignation, DOC also paid Bewick a lump sum payment of $36,000.

Like many of the settlements reviewed by 5 INVESTIGATES, Bewick’s agreement was approved by Minnesota’s Office of Management and Budget.

Commissioner Myron Frans, who ran the department for five years before accepting a similar position this past summer at the University of Minnesota, refused multiple interview requests.

As the top HR official in the state, Frans and the agency appeared to be the driving force behind this practice, which a spokesperson defended as a cost saving measure.

In an email, Chris Kelly said it helps agencies avoid lengthy legal fights after a “risk assessment” determines the firing has the potential to be overturned by an arbitrator.

Gregg Corwin, a labor attorney in Minnesota who has represented public employees for nearly 50 years, says government agencies never used to agree to clean the records of fired employees because of concerns about transparency.

“You’re erasing a public record. It’s different than a private record, Corwin said. “So they were very reticent to do this.”

But Corwin says that started to change in recent years as agencies adopted the legal strategy from the corporate world realizing it was cheaper to have employees leave voluntarily, even if you have to pay them to go away, than to fight them in arbitration.

“Is it better for the public to get rid of that employee or to take the chance, a 50 percent chance, that you might get that employee back…so people make a calculation,” he said. “But it’s not different than what’s done in the private sector. It’s done all the time.”

Jane Kirtley, the University of Minnesota law professor and leading expert on the state’s public data laws, says that kind of rationale minimizes what is a clear public interest in why public employees are terminated.

“Governance is not just about money. It’s about public confidence, it’s about public accessibility and oversight,” she said. “This argument that this is a way of avoiding litigation and avoid(ing) spending money, is a very short sighted argument.”

The unions

The graceful exits are negotiated by public employee unions such as MAPE or AFSCME Council 5, the largest unions in Minnesota, that routinely convince state agencies to remove troubling allegations of misconduct from public records by simply threatening to challenge the termination in arbitration.

“When those employee records are scrubbed, you’re putting future employees and future employers at risk,” said Rep. Pat Garofalo (R-Farmington), who introduced legislation earlier this year that, if passed, would have overhauled the arbitration system. “The problem is the government unions in Minnesota have really written the laws in their favor…and unfortunately it doesn’t just protect the good workers.”

A representative at MAPE did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

In an email, a spokesperson for AFSCME declined to answer questions “in order to protect the privacy of our members.”

Criticism of public employee unions has been aimed mainly at police unions in recent years, including after the death of George Floyd in late May.

Gov. Tim Walz, a lifelong union member, said at the time, “I think it’s going to be important for those of us who are union, and supportive of it, and see the value of them, to stand up and say ‘we cannot craft situations that shield inappropriate behaviors.'”

But Corwin, who represents members of AFSCME, says unions are obligated to fight for workers even in what appear to be extreme circumstances.

“I have been involved in many cases where we were told — we actually have been sued by the employee because we didn’t go to arbitration,” he said.

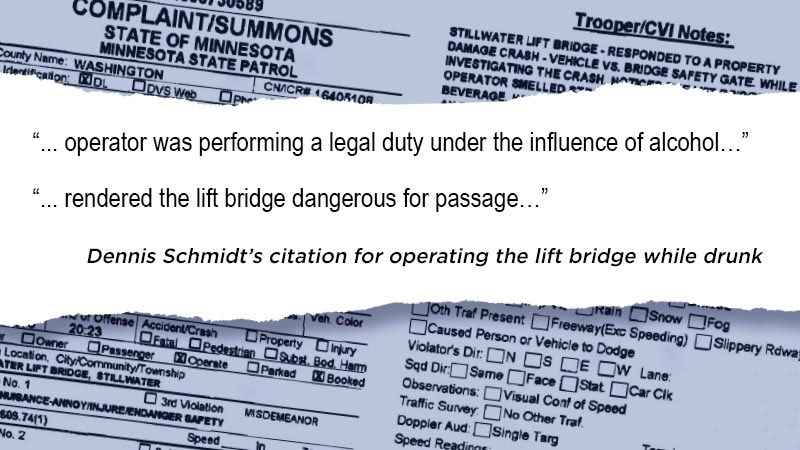

AFSCME challenged the firing of a former MNDOT employee in 2016 months after he was found to be operating the Stillwater lift bridge while drunk.

After responding to an accident on the bridge that June, investigators determined Dennis Schmidt “smelled strongly of an alcoholic beverage, had glazed eyes and behaved similar to an impaired driver,” according to court records.

Schmidt was cited for “performing a legal duty under the influence of alcohol, endangering the public” and making the lift bridge “dangerous for passage.”

Four months later, MNDOT agreed to replace his letter of dismissal with a letter of resignation.

In a brief phone interview, Schmidt acknowledged making a mistake and said he followed the advice of his union.

“I would love to hear the government with a straight face tell you that the public interest is served by concealing to the public the reason for the (employee’s) discharge whose conduct has endangered the public,” Kirtely said. “I would love to hear that. Because I cannot think of what that justification would be. You simply can not reduce everything to what the monetary expenditure is. People’s lives are worth more than just money.”

The controversial legal tactic has been most frequently used by the state’s Department of Human Services, Court Administration, and Minnesota State — the umbrella agency over state colleges.

A maintenance worker at Mankato State was paid $10,500 to resign last year.

George Schmeling initially received a letter of intent to discharge in May 2018 – a little over a month after he was accused of physically and verbally abusing a co-worker, according to court records.

Schmeling was later acquitted on criminal assault charges but was convicted of disorderly conduct. Reached by phone, he admitted resigning after a verbal altercation but denied any physical contact with his former co-worker.

In a statement, a spokesperson said “Minnesota State does not have a practice of ‘cleaning the record’ for former employers” but defended such settlements as a “sound” way to resolve labor disputes.

Since Schmeling’s settlement agreement was not publicly disclosed, the co-worker who complained to the university and obtained an order for protection against him, was unaware that he had been quietly paid to resign.

“I’m saddened, I’m sickened, I’m disgusted by the settlement they reached with him,” Darci Lunde told 5 INVESTIGATES in an interview late last year.

While most state agencies agree to simply reclassify the employees’ termination as a voluntary resignation, agencies have also used creative tactics to explain why the employee is no longer working there.

For example, several employees had their firings changed to lay-offs, even though the settlement agreements specifically state they are not eligible for any benefits associated with lay-offs such as recall status.

Kirtley calls it a blatant misrepresentation.

“You lay people off typically because you don’t have sufficient funds to pay them. That’s not what is going on in a case like this,” she said. “I don’t think we should be lying to the public.”

By characterizing terminations as lay-offs or resignations, agencies have effectively barred anyone from knowing why that employee was initially fired.

Chris Kelly with Management and Budget, says that’s because it’s not considered “final discipline” and state law prevents the release of any records.

But Kirtley says state agencies are aggressively exploiting “loopholes” in the law.

“To disappear information like this, to make it just go away, or wipe it away… It’s basically rewriting history.”