Lawmaker seeks to strengthen mental health response to 911 calls in Minnesota

A state representative is pushing to rewrite a law that requires 911 dispatchers to send trained mental health teams to people in crisis after 5 INVESTIGATES uncovered some counties were still sending law enforcement to those calls.

Signed in 2021, “Travis’ Law” requires dispatchers to “include a referral to mental health crisis teams, where available.”

In Minnesota, every county has access to mobile mental health crisis teams through a program sponsored by the state Department of Human Services.

But a 5 INVESTIGATES review of state data revealed nine counties that didn’t refer a single case to crisis responders in the year and a half after it passed.

Rep. Jessica Hanson (DFL-Burnsville), who wrote “Travis’ Law,” says the reporting illuminates the need for changes.

“My expectation was that, when it passed, it was enforced,” she said during a recent interview. “But unfortunately, as some of your reporting has showed as well, we’re not seeing that in every county.”

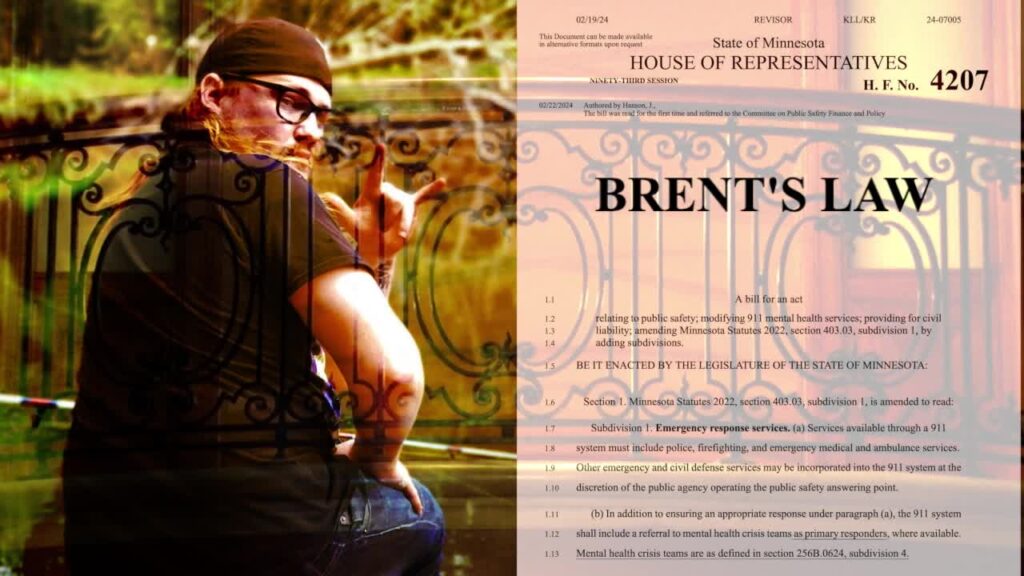

Hanson has introduced House File 4207, a bill that would require 911 dispatchers be trained to recognize mental health crisis calls. It also puts the state in charge of monitoring and enforcing the law, as well as allows the public to sue officials for violating it.

“We do think there should be some consequences and some remedies in place for the counties that choose not to implement such an important law,” Hanson said.

Mental health advocates, like Sue Abderholden, agree the law needs more teeth.

“Without the accountability, it’s not happening,” Abderholden said.

The new bill will be named “Brent’s Law,” in honor of 34-year-old Brent Alsleben, a man who was shot and killed by police after struggling with mental illness.

In 2022, Alsleben’s family called 911 repeatedly after he stopped responding to their calls and texts. His mother, Tara Sykes, told dispatchers her son was diagnosed with bipolar schizoaffective disorder.

A review of incident reports and 911 calls show the Sibley County Sheriff’s Office never sent or requested the assistance of trained mental health crisis teams to help Alsleben.

Months later, he was shot and killed by police during a welfare check.

After Alsleben’s death, Sykes wrote copious notes about her son’s ordeal in a yellow notebook that she keeps near her kitchen table. In that same notebook, she brainstormed ways to make the system better.

“These are my little notes here of what I would like to see changed, what I like to see happen,” she said, flipping through the pages.

The family now hopes Brent’s story will help lawmakers understand the need for changes to the current law. The bill has yet to be scheduled for a hearing in the House Public Safety Finance and Policy Committee.

Brent’s family is hoping to get the bill in front of lawmakers and asking for the public to share their thoughts. You can weigh in on HF 4207 by emailing House Public Safety Finance and Policy Committee chair Rep. Kelly Moller and vice chair Rep. Sandra Feist.