California declared an emergency over bird flu. How serious is the situation?

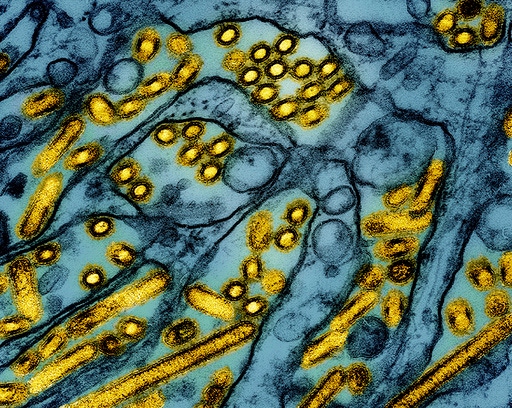

FILE -This colorized electron microscope image released by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases on March 26, 2024, shows avian influenza A H5N1 virus particles (yellow), grown in Madin-Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) epithelial cells (blue). (CDC/NIAID via AP, File)[ASSOCIATED PRESS]

California officials have declared a state of emergency over the spread of bird flu, which is tearing through dairy cows in that state and causing sporadic illnesses in people in the U.S.

That raises new questions about the virus, which has spread for years in wild birds, commercial poultry and many mammal species.

The virus, also known as Type A H5N1, was detected for the first time in U.S. dairy cattle in March. Since then, bird flu has been confirmed in at least 866 herds in 16 states.

More than 60 people in eight states have been infected, with mostly mild illnesses, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. One person in Louisiana has been hospitalized with the nation’s first known severe illness caused by the virus, health officials said this week.

Here’s what you need to know.

Why did California declare a state of emergency?

Gov. Gavin Newsom said he declared the state of emergency to better position state staff and supplies to respond to the outbreak.

California has been looking for bird flu in large milk tanks during processing. And they have found the virus in at least 650 herds, representing about three-quarters of all affected U.S. dairy herds.

The virus was recently detected in Southern California dairy farms after being found in the state’s Central Valley since August.

“This proclamation is a targeted action to ensure government agencies have the resources and flexibility they need to respond quickly to this outbreak,” Newsom said in a statement.

What’s the risk to the general public?

Officials with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention stressed again this week that the virus poses low risk to the general public.

Importantly, there are no reports of person-to-person transmission and no signs that the virus has changed to spread more easily among humans.

In general, flu experts agreed with that assessment, saying it’s too soon to tell what trajectory the outbreak could take.

“The entirely unsatisfactory answer is going to be: I don’t think we know yet,” said Richard Webby, an influenza expert at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

But virus experts are wary because flu viruses are constantly mutating and small genetic changes could change the outlook.

Are cases becoming more serious?

This week, health officials confirmed the first known case of severe illness in the U.S. All the previous U.S. cases — there have been about 60 — were generally mild.

The patient in Louisiana, who is older than 65 and had underlying medical problems, is in critical condition. Few details have been released, but officials said the person developed severe respiratory symptoms after exposure to a backyard flock of sick birds.

That makes it the first confirmed U.S. infection tied to backyard birds, the CDC said.

Tests showed that the strain that caused the person’s illness is one found in wild birds, but not in cattle. Last month, health officials in Canada reported that a teen in British Columbia was hospitalized with a severe case of bird flu, also with the virus strain found in wild birds.

Previous infections in the U.S. have been almost all in farmworkers with direct exposure to infected dairy cattle or poultry. In two cases — an adult in Missouri and a child in California — health officials have not determined how they caught it.

It’s possible that as more people become infected, more severe illnesses will occur, said Angela Rasmussen, a virus expert at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada.

Worldwide, nearly 1,000 cases of illnesses caused by H5N1 have been reported since 2003, and more than half of people infected have died, according to the World Health Organization.

“I assume that every H5N1 virus has the potential to be very severe and deadly,” Rasmussen said.

How can people protect themselves?

People who have contact with dairy cows or commercial poultry or with backyard birds are at higher risk and should use precautions including respiratory and eye protection and gloves, CDC and other experts said.

“If birds are beginning to appear ill or die, they should be very careful about how they handle those animals,” said Michael Osterholm, a public health expert at the University of Minnesota.

The CDC has paid for flu shots to protect farmworkers against seasonal flu — and against the risk that the workers could become infected with two flu types at the same time, potentially allowing the bird flu virus to mutate and become more dangerous. The government also said that farmworkers who come in close contact with infected animals should be tested and offered antiviral drugs even if they show no symptoms.

How else is bird flu being spread?

In addition to direct contact with farm animals and wild birds, the H5N1 virus can be spread in raw milk. Pasteurized milk is safe to drink, because the heat treatment kills the virus, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

But high levels of the virus have been found in unpasteurized milk. And raw milk sold in stores in California was recalled in recent weeks after the virus was detected at farms and in the products.

In Los Angeles, county officials reported that two indoor cats that were fed the recalled raw milk died from bird flu infections. Officials were investigating additional reports of sick cats.

Health officials urge people to avoid drinking raw milk, which can spread a host of germs in addition to bird flu.

The U.S. Agriculture Department has stepped up testing of raw milk across the country to help detect and contain the outbreak. A federal order issued this month requires testing, which began this week in 13 states.

___

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Copyright 2024 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.