US inflation hit a new 40-year high last month of 8.6%

The costs of gas, food and most other goods and services jumped in May, raising inflation to a new four-decade high and giving American households no respite from rising costs.

Consumer prices surged 8.6% last month from 12 months earlier, faster than April’s year-over-year surge of 8.3%, the Labor Department said Friday. The new inflation figure, the biggest yearly increase since December 1981, will heighten pressure on the Federal Reserve to continue raising interest rates aggressively.

On a month-to-month basis, prices jumped 1% from April to May, much faster than the 0.3% increase from March to April. Behind that surge were much higher prices for food, energy, rent, airline tickets and and new and used cars.

The widespread price increases also elevated so-called “core” inflation, a measure that excludes volatile food and energy prices. In May, core prices jumped a sharp 0.6% for a second straight month and are now 6% above where they were a year ago.

America’s rampant inflation is imposing severe pressures on families, forcing them to pay much more for food, gas and rent and reducing their ability to afford discretionary items, from haircuts to electronics. Lower-income and Black and Hispanic Americans, in particular, are struggling because, on average, a larger proportion of their income is consumed by necessities.

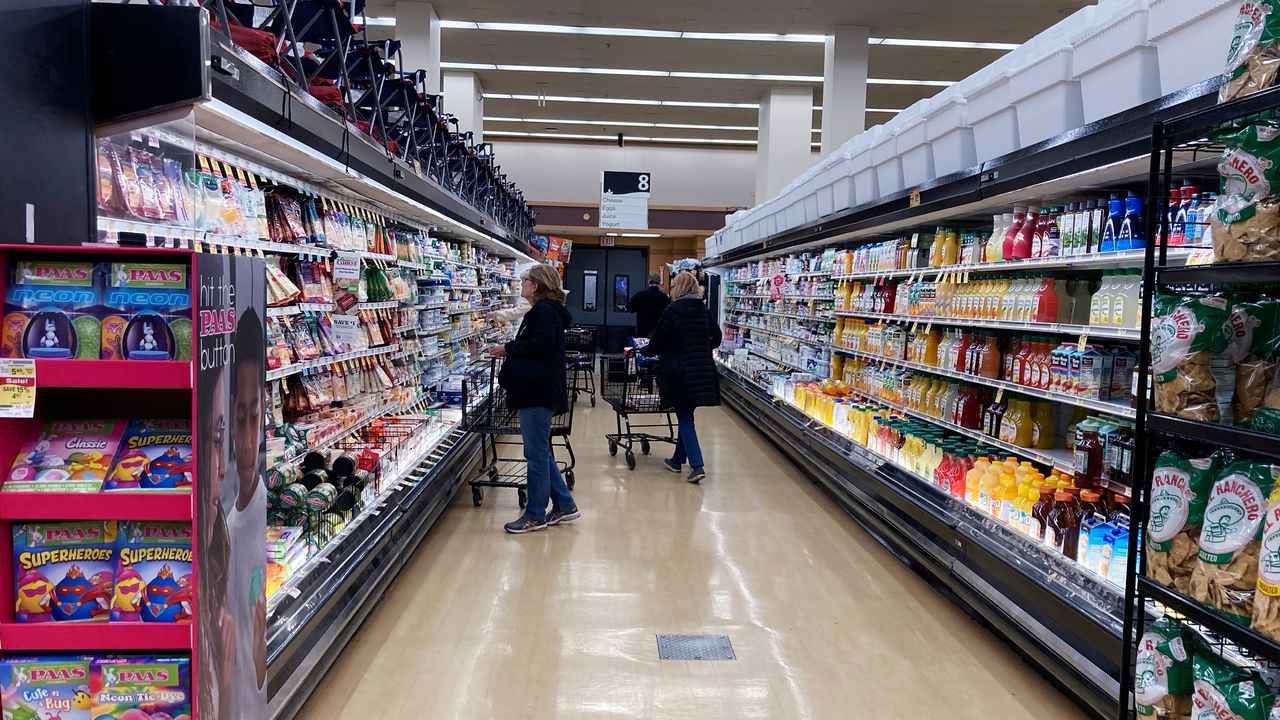

FILE - Customers shop at a grocery store in Mount Prospect, Ill., on April 1, 2022. Consumer prices surged 8.6% last month from 12 months earlier, faster than April’s year-over-year surge of 8.3%, the Labor Department said Friday, June 10, 2022. (AP Photo/Nam Y. Huh, File)

Some evidence in recent weeks had suggested that inflation might be moderating, particularly for long-lasting goods that were caught up in supply chain snarls and shortages last year. But that trend appeared to reverse itself in May, with used car prices rising 1.8% after having dropped for three straight months.

New car prices also rose, a consequence of auto production remaining hamstrung by shortages of semiconductors. And clothing prices increases after having declined in April.

In light of Friday’s inflation reading, the Fed is all but certain to carry out the fastest series of interest rate hikes in three decades. By sharply raising borrowing costs, the Fed hopes to cool spending and growth enough to curb inflation without tipping the economy into a recession. For the central bank, it will be a difficult balancing act.

The Fed has signaled that it will raise its key short-term rate by a half-point — double the size of the usual hike — next week and again in July. Some investors had hoped the Fed would then dial back its rate increases to a quarter-point increase when it meets in September or perhaps even pause its credit tightening.

But with inflation raging hot, investors now increasingly expect a third half-point Fed hike in September. Those rate increases will mean sharply higher borrowing costs for consumers and businesses.

What does this mean for consumers, and how long could Minnesotans be feeling the steep prices?

“My expectation is that inflation is going to be with us for a while. At least a year or two or more. The last time we had inflation up at this level, it took a number of years for the federal reserve to tighten its money supply enough and long enough to convince people that inflation is going to stop. So, the ball is in the court of the Federal Reserve,” said David Vang, a Professor of Finance at the University of St. Thomas.

Vang says the report just verifies what people are experiencing every day, and unfortunately, there’s not a lot anyone can do.

Some advice Vang gave includes limiting your driving, as the cost of gas is one of the most inflated expenses. As of Friday, the average cost of one gallon in Minnesota is $4.74, up $1.89 from last year.

Vang also said if you have a big purchase to make and you have the cash, he says now is probably the time to do that before prices get any higher.

Surveys show that Americans see high inflation as the nation’s top problem, and most disapprove of President Joe Biden’s handling of the economy. Congressional Republicans are hammering Democrats on the issue in the run-up to midterm elections this fall.

Inflation has remained high even as the sources of rising prices have shifted. Initially, robust demand for goods from Americans who were stuck at home for months after COVID hit caused shortages and supply chain snarls and drove up prices for cars, furniture and appliances.

Now, as Americans resume spending on services, including travel, entertainment and dining out, the costs of airline tickets, hotel rooms and restaurant meals have soared. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has further accelerated the prices of oil and natural gas. And with China easing strict COVID lockdowns in Shanghai and elsewhere, more of its citizens are driving, thereby sending oil prices up even further.

Surging inflation has forced Rocky Harper of Tucson, Arizona, to start doing gig work for delivery companies, on top of his regular full-time job with a package delivery service. His main job pays $800 a week, he said, which “used to be really good money and is now just above dirt-poor.”

Harper, 43, said he and his fiancée are delaying marriage because they can’t afford it right now. They’ve cut off Netflix and Hulu. His car’s catalytic converter was stolen recently — an increasingly common theft — for the rare metals they contain that have shot up in price. A repair will cost $1,300.

“With the food, gas and rent — holy cow,” he said. “I’m working a massive amount of overtime, just to make it, just to keep it together.”

In the coming months, goods prices are expected to finally drop. Many large retailers, including Target, Walmart and Macy’s, have reported that they’re now stuck with too much of the patio furniture, electronics and other goods that they ordered when those items were in heavier demand and will have to discount them.

Even so, rising gas prices are eroding the finances of millions of Americans. Prices at the pump are averaging nearly $5 a gallon nationally and edging closer to the inflation-adjusted record of about $5.40 reached in 2008.

Research by the Bank of America Institute, which uses anonymous data from millions of their customers’ credit and debit card accounts, shows spending on gas eating up a larger share of consumers’ budgets and crowding out their ability to buy other items.

For lower-income households — defined as those with incomes below $50,000 — spending on gas reached nearly 10% of all spending on credit and debit cards in the last week of May, the institute said in a report this week. That’s up from about 7.5% in February, a steep increase in such a short period.

Spending by all the bank’s customers on long-lasting goods, like furniture, electronics and home improvement, has plunged from a year ago, the institute found. But their spending on plane tickets, hotels and entertainment has continued to rise.

Economists have pointed to that shift in spending from goods to services as a trend that should help lower inflation by year’s end. But with wages rising steadily for many workers, prices are rising in services as well.