20 years after deadly crash, railroad’s recent misconduct adds to the pain

The doorbell rang at 4:30 in the morning, jolting Cristy and Michael Frazier out of their deep sleep. Cristy hesitantly walked downstairs and opened the door to find the county coroner standing on the front porch with a police officer.

They delivered the news that would forever haunt four families, set off a fierce legal battle, and ultimately expose wrongdoing by one of the largest railroads in the country.

The Fraziers’ 20-year-old son, Brian, was dead. He and his three friends were killed instantly the night before in one of the most tragic train accidents in Minnesota history.

“It became like an out-of-body experience,” Cristy Frazier said. “It was like I knew what they were going to say. I knew their lines, and I knew what my lines should be.”

Two decades have passed, but the pain has not.

“It hurts. I think if there is such a thing as a broken heart, it may mend, but it never closes,” she said. “So it bleeds a little bit on each of those anniversaries.”

In her first interview since the tragedy, Frazier recently reflected on her final moments with her son and the anger she still has for Burlington Northern Santa Fe, the railroad that fought the victims’ families in court for years.

“I think the minute those four children were dead, that a cover up started,” she said.

September 26, 2003

On Sept. 26, 2003, the night of the accident, Brian Frazier attended the Blaine homecoming game to hang out with friends and watch his brother, Tim, play in his last homecoming game.

“I called Brian, and I said, ‘hey, are you still here? I could really use a hug’,” Cristy said, remembering the last time they spoke. “He said, ‘no, we already left. We’re on our way to go pick up a friend.'”

“But I remember saying, you know, ‘I love you,’ and he said, ‘I love you too, Mom.”

An hour later, her son was gone. A BNSF freight train going full speed slammed into his car as it traveled across the Ferry Street crossing in Anoka. Frazier, and his three passengers, Bridgette Shannon, Corey Chase and Harry Rhoades, died instantly.

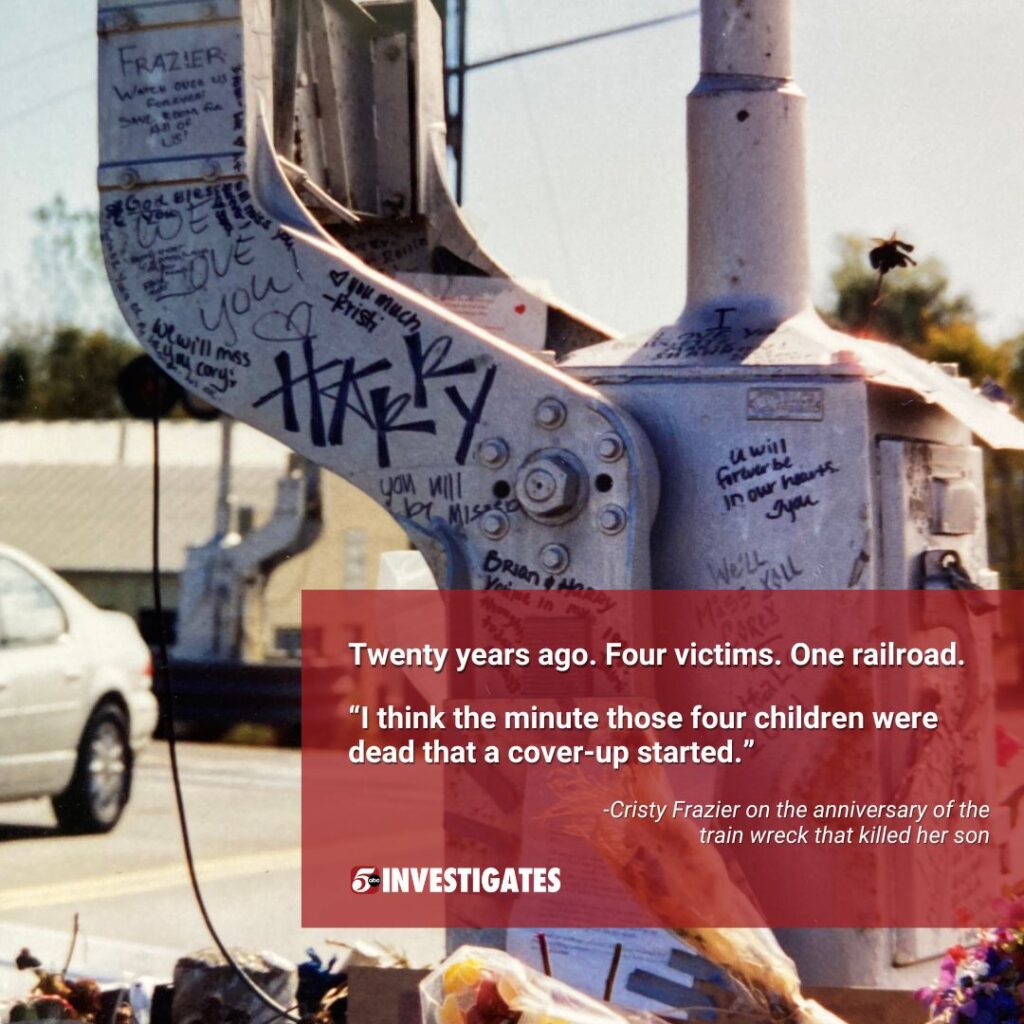

As the community mourned their passing, friends and loved ones turned the crossing arms into a canvas for poems, prayers, and tributes.

Those same crossing arms would later become the center of controversy after the victims’ families sued the railroad, arguing that the signals and arms failed to work properly.

BNSF placed the blame on Brian for trying to outrun the train.

“What kind of a corporation allows a family to believe that their son went around the crossing arm and caused his own death and the death of his friends? Who does that? Who sleeps at night?” Cristy said.

Eight-year fight

The case stretched on for eight years and went all the way to the Minnesota Supreme Court.

This past spring, one of the attorneys representing the families, Sharon VanDyck spoke to 5 INVESTIGATES about what she described as a career case.

“I get teary-eyed just thinking about it. For the families, it was awful – they were so strong,” she said.

VanDyck still keeps the entire case file color-coded and neatly organized in the back of her garage in St. Louis Park.

“I’ve got the whole thing from beginning to the end,” she said.

The case ended in a jury award of $21 million to the families after VanDyck found the railroad altered a key piece of computer evidence that would have said definitively whether the crossing arms were up or down at the time of the crash.

The judge fined BNSF $4 million for its “staggering” amount of misconduct in the case.

“The judge said even if John Grisham wrote this story, no one would believe it,” Cristy said.

Pattern Continues

The railroad’s misconduct in court was part of a larger pattern first exposed by the Star Tribune in 2010. At the time, BNSF claimed it had a new system in place to preserve key evidence in cases that could end in litigation.

As 5 INVESTIGATES reported earlier this year, judges around the country continued to fine, sanction, or admonish the railroad for destroying evidence or retaliating against its employees.

“It makes me really angry,” Cristy said. “I’m tired of big business, being able to manipulate others and pay so they don’t have to own all the damage they’re causing.”

BNSF has not responded to repeated requests for an interview. In response to a previous story by 5 INVESTIGATES, the railroad said that it “disputes whether sanctions were appropriate even in the handful of cases cited” and that most cases involve no allegations of misconduct.

“I think if you’re one person, you can’t fight them, a multibillion-dollar corporation,” Frazier said. “But we all four stuck together.”

Two decades later, Frazier’s anger is matched only by grief.

Her memories of her oldest child are guided by his own words.

“I am mechanically inclined. I am musically talented,” Brian wrote in a poem before his death. It’s called “I am” and lists his skills and aspirations.

“So that’s what we’re missing,” Cristy Frazier said. “All of that potential.”