Local humanitarian aid workers team up to outfit Ukrainian child amputees with prosthetics

[anvplayer video=”5112759″ station=”998122″]

The war in Ukraine is exacting a terrible toll.

An indiscriminate taker of lives and limbs, the casualties are young, old, men, women — and children.

“My friend was killed, and I had to lie on the ground with my legs shot for nine hours,” recalls Tatyana Palamarchuk. “We can hear the bullets fly over our heads. It was very dangerous.”

Palamarchuk spoke with 5 EYEWITNESS NEWS over the phone about the March 5 attack by Russian forces — a day that would change her and her husband’s lives forever.

“We live in a small town, Bucha, in the Kyiv region. It’s not far from the capital,” she says. “We saw Russian helicopters, planes and even on the 4th of March, Russian soldiers in our little town.”

(KSTP)

Palamarchuk says gunfire began across the street from her home, and after a tank shell landed in her front yard, her husband Oleg tried to get rid of it.

“One of the bombs didn’t explode near my house, and the husband took it, wanted to take it away, and it exploded in his hand,” Palamarchuk recalls. “So he got his hand lost.”

The terrified couple — Oleg now bleeding — scrambled to get to the hospital. Instead, while heading that way in their car, things took a terrifying turn.

“We were shot at by Russian soldiers. We got out of the car, we were not injured yet more,” Palamarchuk explains. “My husband decided to walk to the hospital. We couldn’t continue our driving, the car was damaged. It was a dangerous place. They shot everyone in the street, every car, every person.”

Her car was riddled with bullets, and she says she was among those wounded and transported to the hospital.

Doctors would later amputate Oleg’s right hand, shattered by the blast. Palamarchuk suffered bullet wounds in both her lower legs.

“It’s heartbreaking to see how many people in the twenty-first century go through such a terrible time in their life,” said Jacob Gradinar, a Minneapolis prosthetist who moved from Ukraine to Minnesota in 2007. “When they live a peaceful day-to-day life, and suddenly, it gets interrupted.”

The Palamarchuks, both 50 years old, are in the process of recovering in Italy after fleeing from Ukraine.

Tatyana now uses a wheelchair to get around. Oleg is filing paperwork to get a prosthetic hand — a process that could take months.

The Palamarchuks are far from alone. According to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, more than 3,900 civilians and 258 children have been killed since the start of the Russian invasion in late February.

The agency says more than 4,500 civilians and 399 children have been injured in that time.

Experts estimate between a quarter to a third are amputees, but that the actual number could be even higher.

In April, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy announced that between 2,500 and 3,000 Ukrainian soldiers had been killed, while 10,000 had been injured.

Humanitarian aid workers say the war itself is stopping the limb-loss wounded from getting the help they need.

“All production for prosthetics stopped for the most part in Ukraine, they’re relying on outside sources to connect with,” says Monte Schumacher, a U.S. Army Special Forces veteran originally from Fargo, and the grandson of Ukrainian immigrants. “Expensive materials like titanium that are related to creating higher quality prosthetics. It’s just completely absent in the country right now.”

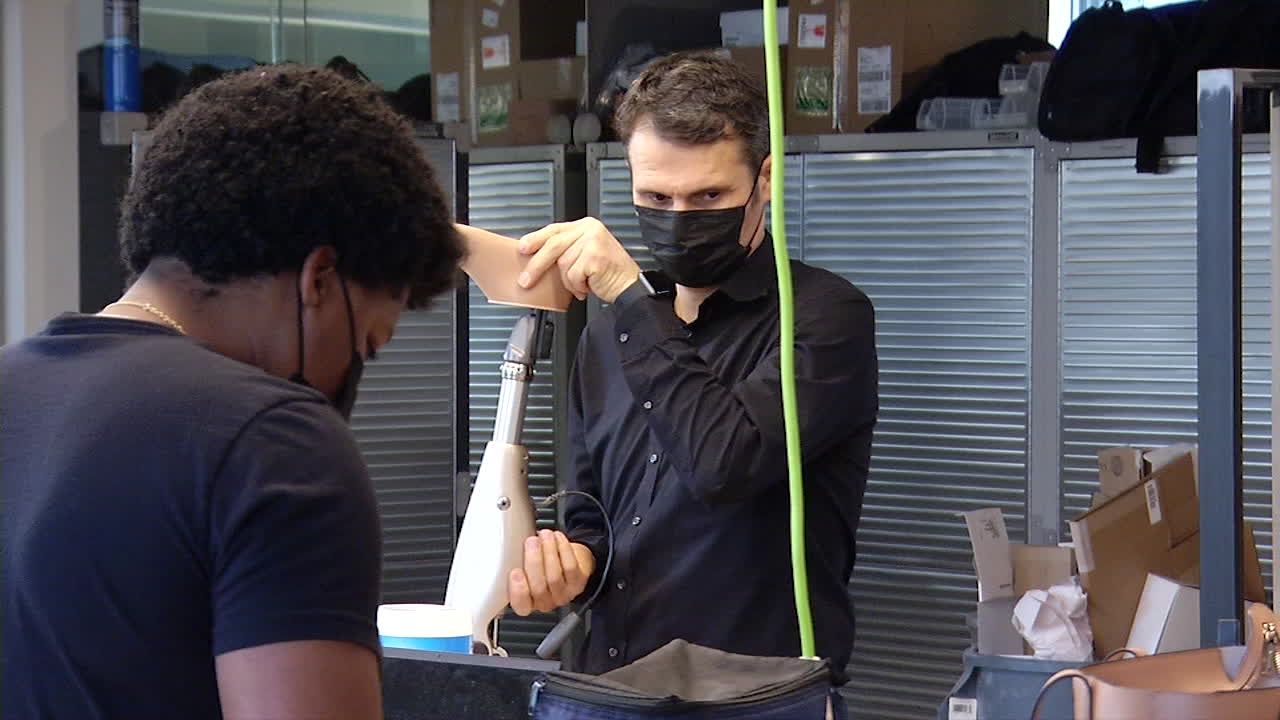

Gradinar — the office manager for the Minneapolis location of Limb Lab, a prosthesis provider — says in post-Soviet Union countries like Ukraine, quality prostheses have been difficult to find, even before the war.

Now, he says, there’s a waiting list that can last months.

“Even with Europeans helping and locals, there are a lot of people in long lines, on waiting lists for getting prosthetics done,” Gradinar notes. “(One) person that we heard actually got injured before the war in October, and he still hasn’t gotten a prosthetic.”

Peter Nordquist, a humanitarian aid volunteer from Edina, has been working in Poland and Ukraine since early April.

He hopes to help children recovering from limb-loss wounds.

“It’s really heart-wrenching to see these young kids having bombs blowing their legs off,” Nordquist said. “Poor children — 8, 9 and 10 years old — and from the knee or above the knee, they simply don’t have a leg.”

Nordquist and Schumacher have started a crowdfunding campaign called Courage Ukraine.

The two are networking with officials in cities like Lviv to find ways to solve the prosthesis shortage.

“They approached us with, ‘Is there something we could do to bring the expertise from the United States here or bring the children back home to have medical care provided to them?'” Nordquist says.

He notes the plan is to start small, hoping to raise enough money to bring six to 10 children to the U.S.

“We’re looking at the ability to transport some of these amputees,” Schumacher said. “If they’re children, of course, they’ll have to travel with their parents, and they would come to the U.S. and possibly spend a month or more while they’re fitted and some of the rehabilitation process occurs.”

Both men also hope to eventually bring prosthetic experts and U.S.-made parts to the Poland-Ukraine region.

Gradinar says he wants to join in that effort. He’s started a crowdfunding effort of his own, called Prosthetics for Ukrainians.

Gradinar is hoping to help Ukrainians with limb-loss injuries, by raising funds for airfare to the U.S., places to live during treatment, rehabilitation and new prostheses and materials.

“I will do my best to go and help and improve the quality of prosthetic care, and bring some donated parts,” he declares. “And bring some newer parts from manufacturers to get these people as soon as possible back to the routine of life.”

Nordquist, Schumacher and Gradinar say they’re now connecting to discuss plans on how to help Ukrainians with limb-loss injuries.

As for the Palamarchuks, Gradinar says they’ve applied for visas to the U.S.

He says he wants to provide free prosthetic services for them, if and when they’re able to get here.

Palamarchuk says she’s thankful for the efforts of those trying to help her family and so many others whose lives have been forever changed by the war.

“I think they are great people with great heart. It is very good that somebody is trying to help,” she says. “A lot of people trying to help Ukraine nowadays. Europeans, Americans, all people around the world, and I’m grateful.”