‘He is one of my heroes.’ WWII and US Navy vet John Hagen honored by fellow vets

[anvplayer video=”5099464″ station=”998122″]

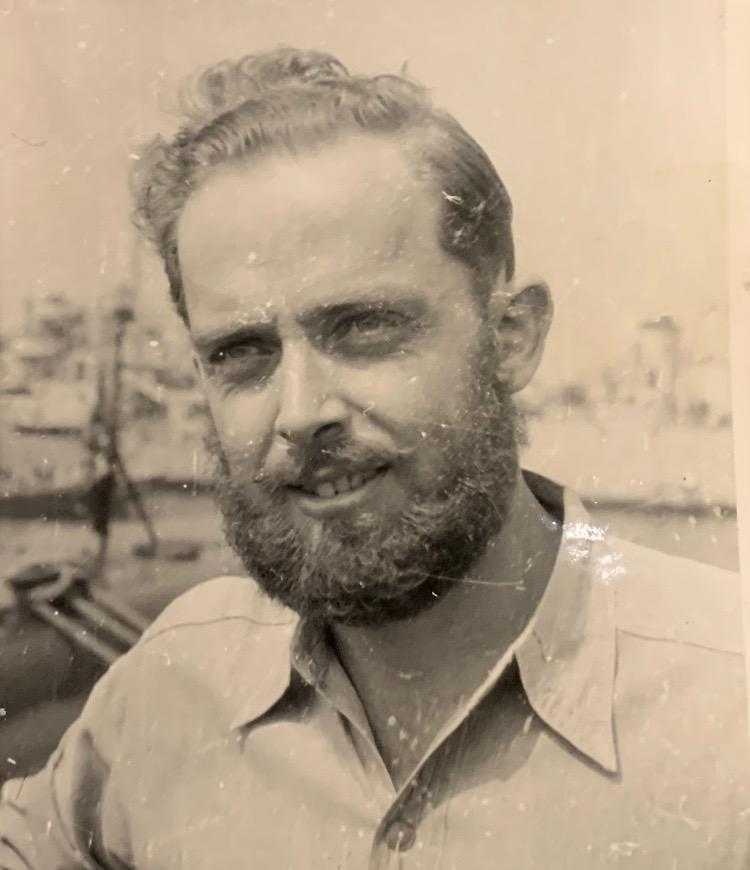

John Hagen, 96, a decorated World War II veteran, proudly wears the patches and pins that symbolize his service.

He showed 5 EYEWITNESS NEWS those decorations at his Golden Valley home, including the submarine warfare insignia – also known as the “dolphin pin.”

“Once a submarine sailor, you’re always a submarine sailor,” he said. “You’re a sub-mariner.”

This week, Hagen’s fellow Navy submarine veterans plan to honor him in a special way.

“He is one of my heroes,” declared Kenneth Tupper, a submariner from the Vietnam era. “It was a tremendously different submarine force, back before the snorkels, back in World War II, before all the equipment, all the radars. The torpedoes had problems. And you know, we lost 52 submarines during World War II.”

96-year old John Hagen, a decorated World War II veteran, proudly wears the patches and pins that symbolize his service. Hagen, who served in WWI and went on to serve on U.S. Navy Submarines is to be honored this week by his fellow Navy Veterans.

In 1943, Hagen was a 17-year-old from St. Louis Park who would serve in the South Pacific and then, after the war, on submarines.

He was part of a generation that fought in battles that spanned the globe.

“John and all the World War II people are the greatest generation,” said John Barnes, the commander of the Minneapolis-St. Paul chapter of the United States Submarines Veterans, Incorporated, or USSVI, for short. “They did what they had to do and prevailed. They got us our freedom that we see today.”

It was a generation that faced the horrors of war but were ready to join in the fight.

“I went in the Navy in ’43,” Hagen recalled. “A bunch of us in high school wanted to go into the Marine Corps, and my dad said absolutely not. He wouldn’t sign.”

So he went to sea, trained at sonar school, and was shipped to Hawaii.

While waiting on a ship assignment, he was ordered to go to Pearl Harbor nearly two years after the attack by the Japanese empire.

“The Oklahoma battleship had just come off the bottom,” Hagen said. “And we were the first crew to go on it, to clean it up and help.”

He says what they found inside the once-submerged ship was horrific and heartbreaking, including the remains of some of the 429 men killed on board.

“Two of us were assigned to an officer and went through the compartments and opening lockers and collecting, and he wrote down everything, what the locker was and what was in it,” Hagen remembered.

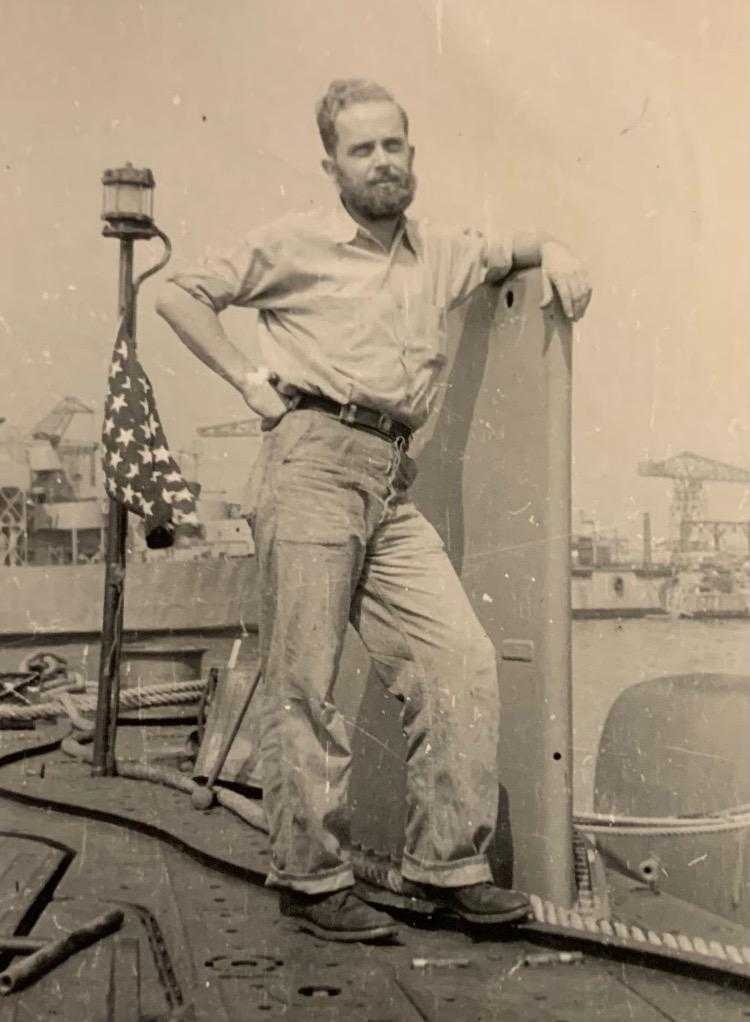

He served on two destroyer escorts, the USS Darby and the USS Martin.

Hagen still has an American flag from the Darby, now kept in a triangular wooden case, and a knife with a handle made partly with metal from downed fighter planes.

“We had a carpenter that would take the knife and had scavenged metal and aluminum and stuff from wrecked airplanes,” he said. “They put the handle on it, and I carried that all during the war.”

Hagen wasn’t even 21 years old when he first encountered a vast armada of ships in places that would become known to the world: Guadalcanal, the Philippines, and the Marshall Islands.

“Seven battleships, and I think twelve carriers and everything in between,” he said. “Battleships came under attack quite often, at night, with the Japanese planes and things.”

Hagen said he was fortunate that he survived the war and was never wounded.

“I was very fortunate,” he said. “I had a wonderful career … came out of it with all four arms and legs.”

In 1945, at the war’s end, Hagen’s life changed again with a simple question from a Navy commander.

“He said, how many of you guys want to go to submarine school,” he smiles. “Me,” Hagen says, raising his hand. “That’s how we got into submarines.”

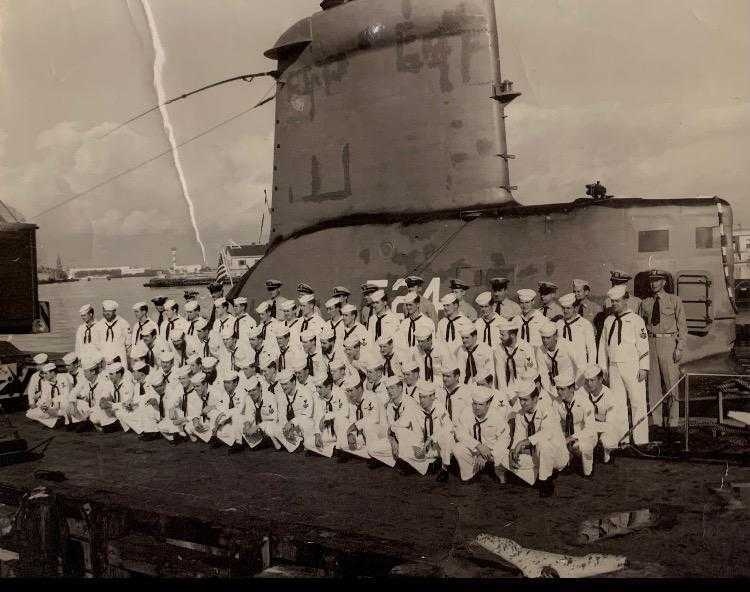

By 1947, Hagen had completed a process the Navy calls “qualifying.”

He was awarded his “dolphin pin” for his thorough knowledge of submarines.

“Memorizing everything there is on the boat,” Barnes, a qualified submariner, noted. “What to do with each person’s job. You need to be able to handle all that, and that’s six months, a year on some boats.”

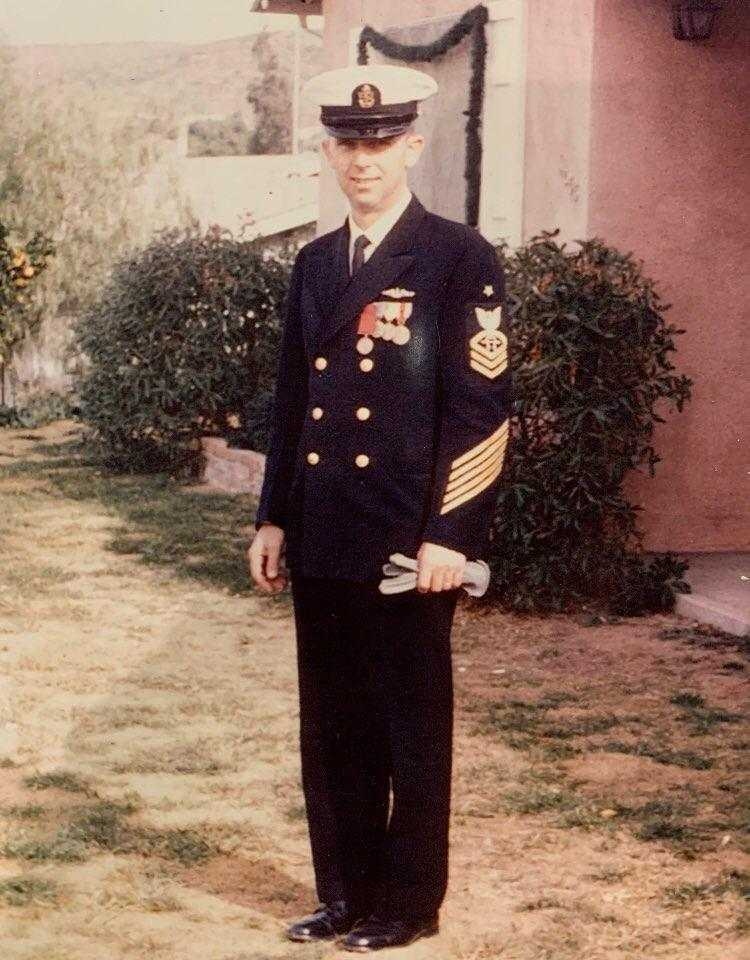

Hagen retired from the Navy in 1964, as a Sonar Technician Senior Chief, after a 20-year naval career.

We asked what made him stay.

“I liked it,” Hagen said. “I was on submarines, and it’s the greatest bunch of guys in the world. You can’t imagine … every time the diving alarm goes, sixty other guys you know are doing their job, and you don’t worry about it.”

Those who have won their “dolphin pins” are considered an elite group.

A band of brothers under the ocean waves.

Tupper also qualified in submarines, put it like this: “When you’re out at sea, and everything can go wrong, and you have fifty or sixty other guys that knows as much as you do, and how to fix what can go wrong, it’s kind of a peaceful feeling, actually.”

Which brings us to present day.

This Friday, Hagen will be honored by his fellow submarine veterans at an invitation-only breakfast at VFW Post 1350 in St. Paul.

He’s to receive a special certificate to celebrate the 75th anniversary of his qualifying in submarines.

The Holland Club organizers, whose club name comes from the name of the first U.S. Navy submarine, say Hagen is one of a handful of people to receive this honor.

“I think it’s pretty nice,” the 96-year-old man smiled. “But nothing special. I’m just very fortunate to live this long,” he added with a chuckle.

It’s the pin that unites this group – and everything it symbolizes.

“To earn these is a big thing,” Barnes said. “John, not only has he survived a long time, [and] he’s been very generous with our group. Just a good brother. That’s what we are, [and] we’re all brothers. John’s our older brother.”

If you would like to learn more about the United States Submarine Veterans, you can contact them via email at office@ussvi.org or call them at 1-877-542-3483.