Doubling down on light rail expansion: Critics question cost of taking on two billion-dollar projects at the same time

[anvplayer video=”5123617″ station=”998122″]

As the multi-billion dollar Southwest light rail project became bogged down with delays, cost increases, and questions about damage to nearby condo buildings in Minneapolis, homeowners on the city’s north side were watching closely.

The Metropolitan Council recently approved a plan to extend the Blue Line to run through the Lyn Park neighborhood and past Kathy Neitzke’s home on Lyndale Avenue.

“I just don’t have trust in what they’re planning for our community,” Neitzke said.

Residents continue to raise concerns about crime, safety, and access to their neighborhood, that some describe as a “piece of suburbia” in the city.

But Neitzke and others are also questioning the prudence of pushing forward with another billion-dollar light rail project when construction on Southwest light rail is still years behind schedule.

(KSTP)

“They’re using federal money, tax money, our livelihoods, our safety,” Neitzke said. “That’s why I say we need to pause here. We need to get better decision making.”

The Met Council and Hennepin County voted last month to move forward with design and engineering for the Blue line even though those agencies have yet to explain how they will come up with the $500 million needed to finish the Southwest light rail project.

Promises of Accountability

Reva Chamblis, Met Council Member for District 2, is among those who say they can and should complete both light rail projects.

“I think the big word there is accountability,” Chamblis said in an interview with 5 INVESTIGATES. “We are accountable to get that project finished… We’re accountable to residents, we’re accountable to businesses, we’re accountable to the people who are going to benefit from the light rail projects.”

Leaders say it’s too soon to know exactly how much the Blue Line extension will cost, but the man who helped build the original Blue Line 20 years ago says it’s not unreasonable for taxpayers to be skeptical.

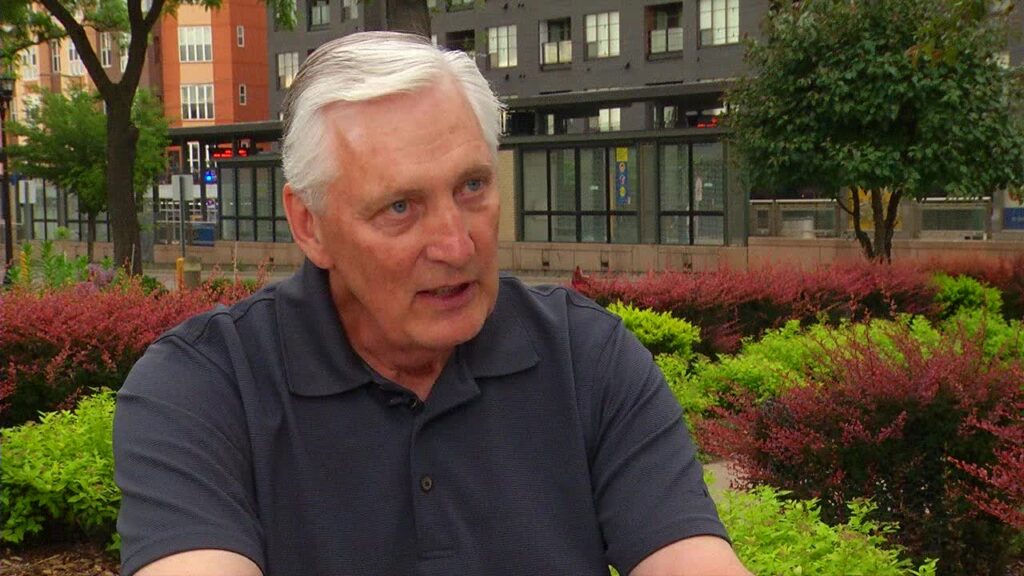

El Tinklenberg is a former MnDOT commissioner who oversaw the Twin Cities’ first light rail project, which started running trains in 2004.

“We were acutely aware of the fact that this being the first one, we had to make this successful because it was going to be what led to the next one and the next one,” Tinklenberg said.

But he now worries that the Met Council has lost some of the public’s trust as the Southwest light rail project, an extension of the Green Line, is still incomplete and the subject of a state audit.

“I don’t think they see the current project being orderly enough to justify jumping into another one,” Tinklenberg said. “It would be a little like somebody is building you a home, and they come to you and say, ‘there are some problems, and there are some delays, and oh, by the way, it’s going to cost twice as much, but the good news is next week we’re going to start on your cabin!'”

Community impact

Supporters of the Blue Line extension say it is needed to provide more access and opportunity to historically disenfranchised communities.

Homeowners who packed a community meeting with Met Council and Hennepin County project managers in May questioned the government’s promises to be accountable.

Some say they worry about the kind of destruction that impacted the historically Black Rondo neighborhood in St. Paul during the construction of Interstate 94.

“You’re bringing the train to the wrong people,” said Spike Moss, a community activist in Minneapolis. “We finally get a neighborhood with decent homes, and you want to bring it down through there?”

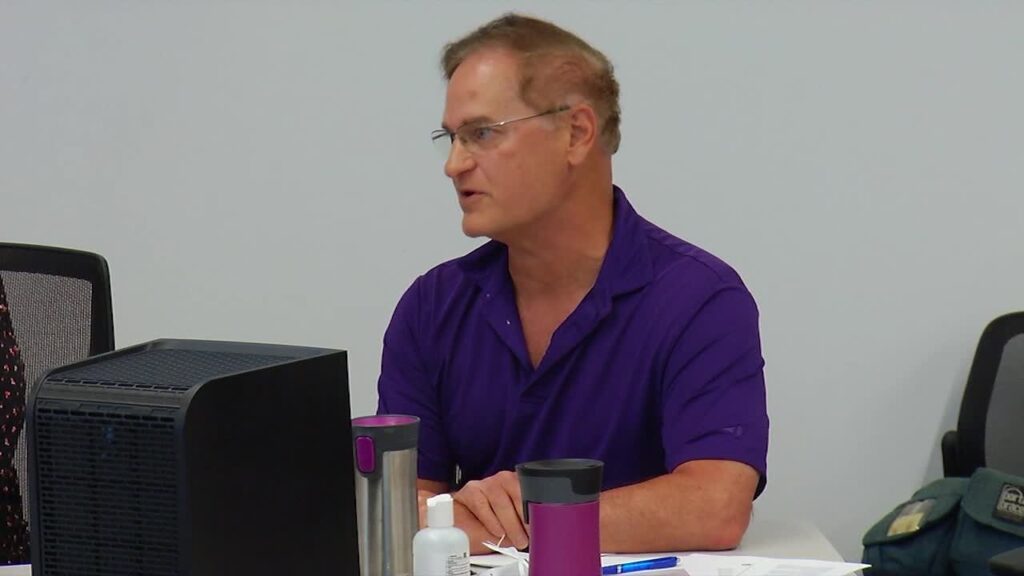

Dan Soler, a senior program administrator with Hennepin County, told the anxious crowd that this time would be different.

“Our leaders are very much interested in building this transportation improvement for north Minneapolis, not through north Minneapolis,” Soler said.

Hennepin County Commissioner Irene Fernando declined a 5 INVESTIGATES request for an interview, but in a statement said the Blue Line Extension is “positioned to serve among the most racially and economically diverse communities.”

“I have not pushed for a specific alignment, and I will not in the future. I instead have worked to ensure community feedback informs the project as we move forward,” said Fernando who is also a member of the METRO Blue Line Extension Corridor Management Committee.

“The more that we engage people, the more we show that we are accountable to getting our projects done in a fashion that includes everyone and benefits our entire communities along the corridor, the more that trust will be built,” Chamblis said.

Mayors push back

The mayors of two cities on the Blue Line extension cited “trust issues” in a recent meeting where they voted against the proposed route.

Bill Blonigan of Robbinsdale said project managers should not have abandoned the original plans to run light rail trains along the existing BNSF freight corridor after they were unable to come to an agreement with the railroad company.

The Blue Line Light Rail Extension Corridor Management Committee last week declined to consider a resolution from Robbinsdale that would have called on Governor Tim Walz and Minnesota’s congressional delegation to try to bring BNSF back to the bargaining table.

Crystal Mayor Jim Adams also raised concerns about pedestrian access, additional public transit resources within the city, and the loss of vehicle traffic lanes if the planned route becomes a reality.

“I think the community, in many ways, doesn’t support this,” Adams said.

Chamblis disagrees.

“I was shocked when I heard that, and that is not the feeling that I have gotten,” Chamblis said. “We have done some very deep engagement in Crystal, from businesses, and from residents.”

She also points to development already growing around planned stops on the Green Line extension in Eden Prairie as reasons for optimism.

But that project is already four years behind schedule – trains are not expected to start running there until 2027.

The plan to complete the Blue Line extension and start service by 2028 still has to get past a vote of cities along the route, known as municipal consent, as well as an agreement with the federal government to fund a portion of the project.

“Does everybody support it? No. But we have to do our best to make sure that our state, our county, our city, our residents, and businesses can understand the benefits of this project and why it’s important for us to move forward,” Chamblis said. “We need to finish what we’ve started.”