U of M researchers studying how young people, immunocompromised respond to the vaccines

[anvplayer video=”5052869″ station=”998122″]

Small swabs are essential to tracking how effective the Moderna vaccine is. Each will carry nasal samples to a lab at the University of Minnesota Medical School.

A team of researchers have joined the national Prevent COVID U study. There are more than 40 sites across the country participating but the U of M is the only location in the four-state border region.

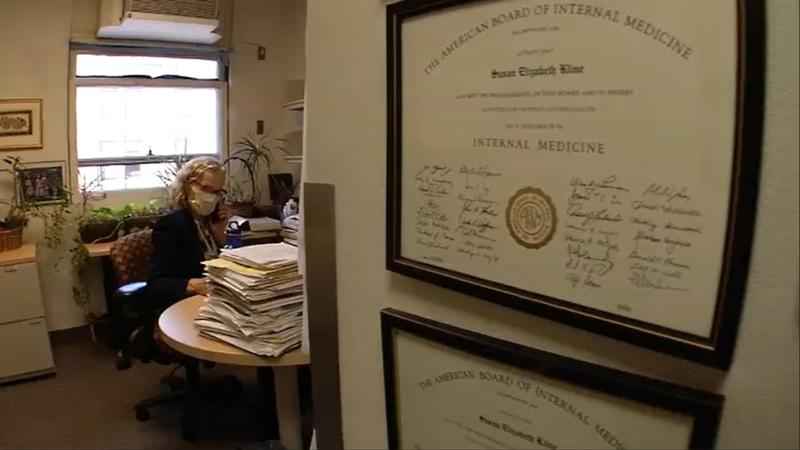

“I think it’ll tell us a lot that we haven’t really discovered in detail to this point,” said Dr. Susan Kline, an infectious disease physician with the University of Minnesota Medical School and M Health Fairview.

Dr. Kline is the local lead investigator of the study, which focuses on people age 18 to 29.

[KSTP]

“Young people I think have a lot of social contacts,” said Dr. Kline. “As we know from our local health department data, this is actually the age group that has higher rates of COVID-19.”

Her team hopes to enroll 150 young people who have not received a vaccine or tested positive for COVID-19. Participants do not need to be students at the University.

Those who want to get the vaccine will be randomly selected to either get the Moderna shots right away or receive the standard of care, which means they can choose to get any vaccine at any time.

“They can access that on their own, if they haven’t gotten vaccinated four months into the study they’ll be given the Moderna vaccine as well,” said Dr. Kline. “Then there’s a third group of participants who don’t want to be vaccinated and yet are willing to participate.”

The third group will not receive a vaccine.

All participants will be asked for periodic blood samples and daily nose swabs over the course of four to five months.

If anyone tests positive, the research team will work to gather samples from a web of their close contacts.

“I’m really hoping to learn how likely are people who have been vaccinated first of all to acquire the infection compared to those who weren’t vaccinated,” she said. “How heavy is the amount of virus in their nose? […] Even if you have asymptomatic infection, how likely are you to spread it to others?”

The trial is being conducted through the COVID-19 Prevention Network (CoVPN), which hopes to enroll 18,000 people across the country.

“The virus is transmitted differently, in different parts of the country, at different time periods,” said Dr. Kline. “As we’ve seen this summer, some of the heaviest transmission has been in the South for instance but last fall, Minnesota was sort of one of the highest sites in the country and so there will be these seasonable variations in these different regions. I think having representation in all of the different regions is important.”

With the delta variant, she also expects they will see more cases of transmission.

The new strain of the virus is also affecting another study at the University of Minnesota Medical School.

“Delta has definitely thrown a wrench into things,” said Dr. Amy Karger, a clinical pathologist with the University of Minnesota Medical School and M Health Fairview.

Dr. Karger is studying the immune response to the vaccines. It’s a national study sponsored by Serological Sciences Network (SeroNet), which is “a major component of the National Cancer Institute’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic”, according to the University.

Her research looks at how those with compromised immune systems respond to all of the vaccines.

“We were specifically tasked to look at three immunocompromised populations – HIV patients, transplant patients and then patients with a history of cancer,” said Dr. Karger. “Part of the reason we chose the groups we did, we thought there was excellent subspecialty care in those areas of cancer, and transplant and HIV here at the University of Minnesota and we knew that a lot of patients come here for that care.”

Enrollment started in June with participants who had not yet received a vaccine. The team recruited people with both compromised and normal immune systems in order to compare the two groups.

“We’re trying to measure samples one to three months after vaccination, that’s kind of when you expect the immune response to be at its peak, and then we want to follow that after that approximately every six months to see its decline over time,” explained Dr. Karger.

The study will last for two years.

“We’ve just started looking at our preliminary data, we haven’t published anything yet but it certainly does appear in our cohorts so far there are some people who don’t have as good immune response as others,” said Dr. Karger. “We’re really going to spend the next month or two looking more deeply at that data to try to sort out what are the contributors to a poor immune response to the vaccine.”

She said the research is important in determining how to move forward with vaccinations.

“I think the ultimate goal is if we can figure out why people aren’t responding, maybe we can modulate some of those risk factors or address them or come up with other vaccination strategies,” she said.

The team is now adding another group of participants as well to adjust to the changing recommendations. They are seeking people who are immunocompromised, vaccinated, and will be receiving their third shot.

“This really gives us an opportunity to recruit a whole fresh batch of participants now that people are getting the third dose,” said Dr. Karger. “We’d like to be on the cutting edge of figuring out how good of a response we’re going to get from that additional vaccine.”

To enroll in Dr. Karger’s study, click here.

To enroll in Dr. Kline’s study, click here.