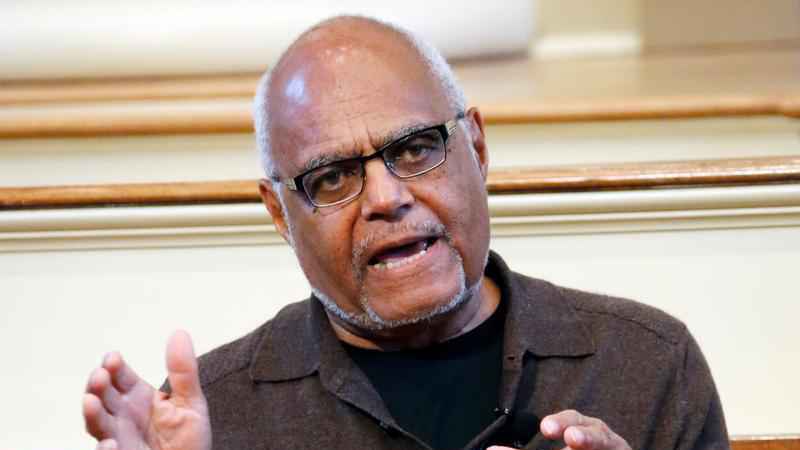

Civil rights activist Robert Moses dead at 86

2014 file photo shows Robert "Bob" Moses, a director of the Mississippi Summer Project and organizer for the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) answers questions about Freedom Summer in 1964 during a national youth summit hosted by the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History, at the Old Capitol Museum in Jackson, Mississippi.[Rogelio V. Solis/Associated Press]

Robert Parris Moses, a civil rights activist who endured beatings and jail while leading black voter registration drives in the American South during the 1960s and later helped improve minority education in math, has died. He was 86.

Moses worked to dismantle segregation as the Mississippi field director of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee during the civil rights movement and was central to the 1964 “Freedom Summer” in which hundreds of students went to the South to register voters.

Moses started his “second chapter in civil rights work” by founding in 1982 the Algebra Project thanks to a MacArthur Fellowship. The project included a curriculum Moses developed to help poor students succeed in math.

Ben Moynihan, the director of operations for the Algebra Project, said he had talked with Moses’ wife, Dr. Janet Moses, and she said her husband had passed away Sunday morning in Hollywood, Florida. Information was not given as to the cause of death.

Moses was born in Harlem, New York, on January 23, 1935, two months after a race riot left three dead and injured 60 in the neighborhood. His grandfather, William Henry Moses, has been a prominent Southern Baptist preacher and a supporter of Marcus Garvey, a Black nationalist leader at the turn of the century.

But like many Black families, the Moses family moved north from the South during the Great Migration. Once in Harlem, his family sold milk from a Black-owned cooperative to help supplement the household income, according to “Robert Parris Moses: A Life in Civil Rights and Leadership at the Grassroots,” by Laura Visser-Maessen.

While attending Hamilton College in Clinton, New York, he became a Rhodes Scholar and was deeply influenced by the work of French philosopher Albert Camus and his ideas of rationality and moral purity for social change. Moses then took part in a Quaker-sponsored trip to Europe and solidified his beliefs that change came from the bottom up before earning a master’s in philosophy at Harvard University.

Moses didn’t spend much time in the Deep South until he went on a recruiting trip in 1960 to “see the movement for myself.” He sought out the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference in Atlanta but found little activity in the office and soon turned his attention to SNCC.

“I was taught about the denial of the right to vote behind the Iron Curtain in Europe,” Moses later said. “I never knew that there was (the) denial of the right to vote behind a Cotton Curtain here in the United States.”

The young civil rights advocate tried to register Blacks to vote in Mississippi’s rural Amite County where he was beaten and arrested. When he tried to file charges against a white assailant, an all-white jury acquitted the man and a judge provided protection to Moses to the county line so he could leave.

He later helped organize the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, which sought to challenge the all-white Democratic delegation from Mississippi. But President Lyndon Johnson prevented the group of rebel Democrats from voting in the convention and instead let Jim Crown southerners remain, drawing national attention.

Disillusioned with white liberal reaction to the civil rights movement, Moses soon began taking part in demonstrations against the Vietnam War then cut off all relationships with whites, even former SNCC members.

Moses worked as a teacher in Tanzania, Africa, returned to Harvard to earn a doctorate in philosophy, and taught high school math in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Later in life, the press-shy Moses started his “second chapter in civil rights work” by founding in 1982 the Algebra Project.

Historian Taylor Branch, whose “Parting the Waters” won the Pulitzer Prize, said Moses’ leadership embodied a paradox.

“Aside from having attracted the same sort of adoration among young people in the movement that Martin Luther King did in adults,” Branch said, “Moses represented a separate conception of leadership” as arising from and being carried on by “ordinary people.”