How a 1971 arrest laid the groundwork for the state investigation into Minneapolis Police

Peggie Carlson looked over the photo albums spread across her dining room table. Among the images of family gatherings and school portraits, she found two pictures of her younger brother, Randy Samples.

The first shows a small boy with a wide, gap-toothed smile. In the second photograph, the smile is gone.

“He looks so serious in this picture,” said Jennifer Cummins, Peggie’s sister.

But the picture that would change Randy’s life and the Samples’ family isn’t in one of the photo albums.

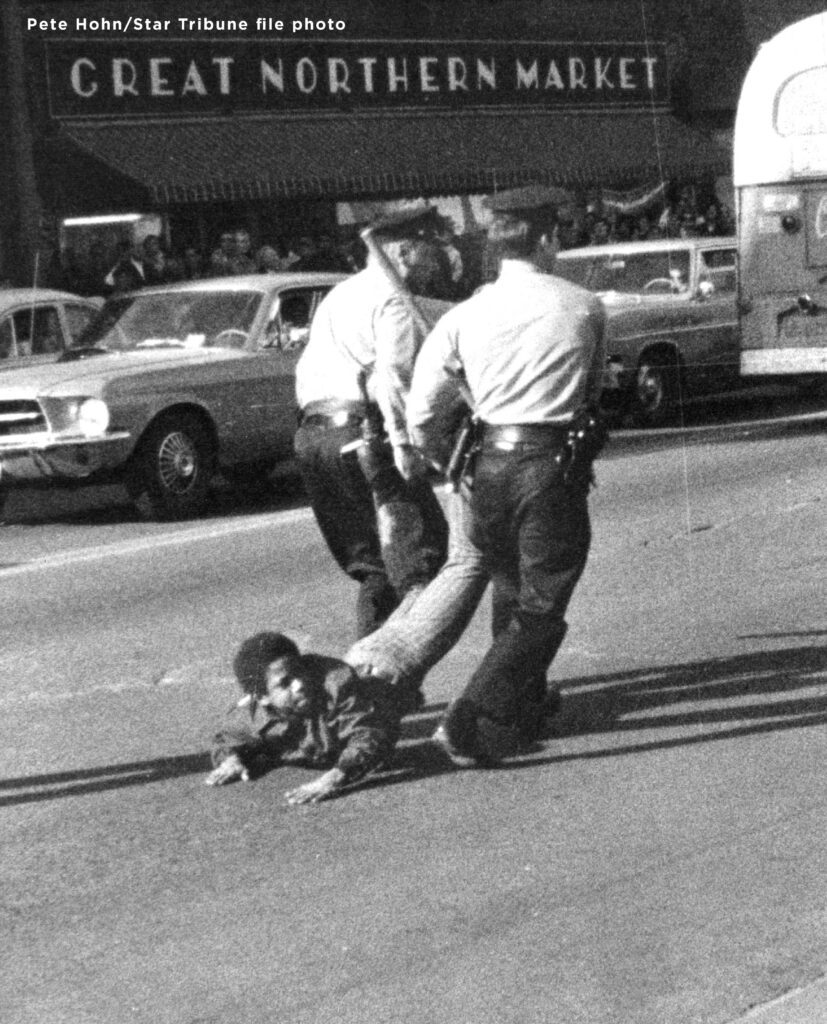

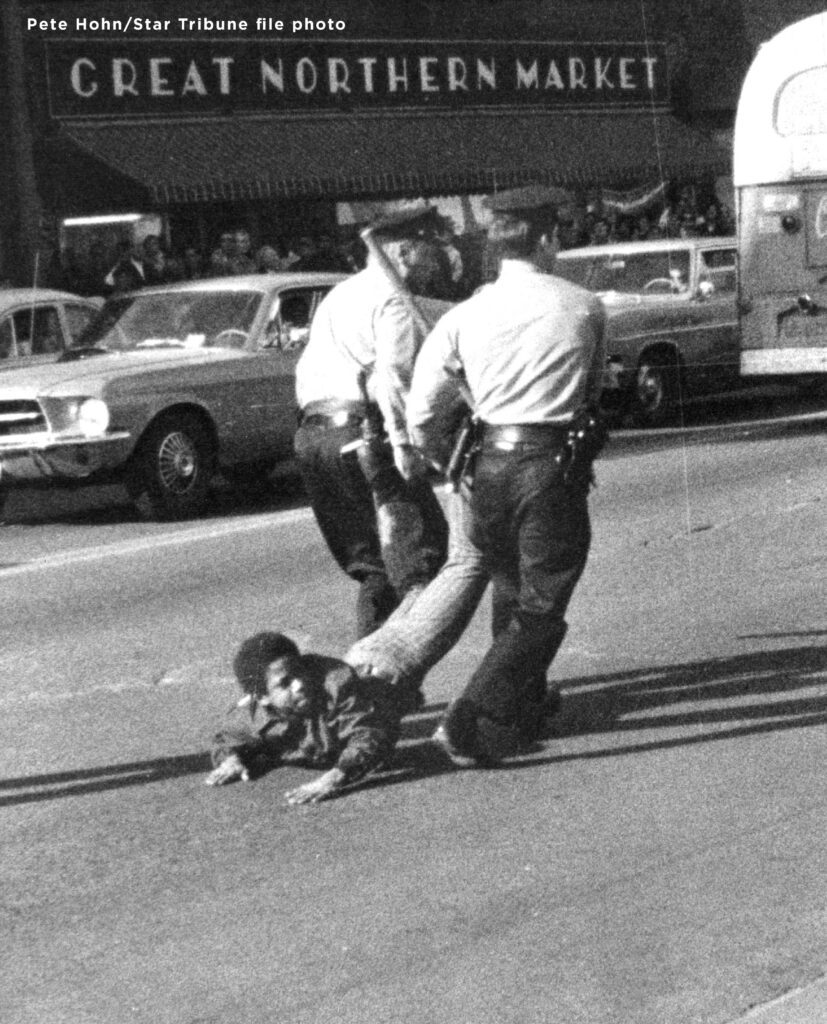

On April 12, 1971, the then-Minneapolis Tribune published a photo of two Minneapolis Police officers dragging an unidentified Black boy, by his ankles, down Hennepin Avenue. The small child is on his stomach, his hands scraping against the pavement, as a crowd on the sidewalk looks on.

The boy was Randy Samples. He was 12 years old.

landmark legal battle between Minneapolis and the state’s Department of Human Rights.

Courtesy: Pete Hohn/Star Tribune file photo

His arrest became a pivotal moment in the fight for civil rights in Minnesota and resulted in a landmark state Supreme Court decision.

Legal experts argue it also laid the foundation for the state to investigate the Minneapolis Police Department more than 50 years later after the murder of George Floyd.

In April, the Minnesota Department of Human Rights found MPD officers engage in a pattern or practice of race discrimination. The 72-page report detailed what investigators say are systemic failures going back a decade.

But longtime Minneapolis residents say that investigation—and the failures it identified—can be traced back half a century – to the picture of Randy Samples.

“I think that we’ve taken a giant step nowhere,” Carlson said.

The arrest

On a Saturday afternoon in 1971, Randy Samples walked down Hennepin Avenue and noticed a large crowd gathering outside of Rifle Sport, an amusement arcade.

The Tribune reported at the time that a fight that had broken out inside of the arcade spilled out onto the street. Peggie says Randy wandered over to see what was going on right as Minneapolis Police released K-9s to break up the group.

“Even though there was a relatively big crowd of people, predominantly white, the dogs went right for Randy,” Carlson said.

After Randy was knocked to the ground, the officers dragged him nearly 30 feet to their squad car.

“I remember being concerned about how he was dragged and hoping his hands were okay,” said Cummins.

When Randy’s parents picked him up from the police station, he told them the officers used racial epithets, including the N-word, to describe him and the other African Americans in the crowd.

“When I say Randy went in to buy a poster a little boy and he came out an old man, I think all of us aged a bit that day,” Carlson said. “I think I became much more aware of what goes on in Minneapolis.”

No accountability

Months after Randy’s arrest, Robert and Mary Jane Samples found the fight for accountability for their son would be an uphill battle.

In a letter to the editor published in June 1971 in the Minneapolis Tribune, Randy’s father wrote that he was unable to file a complaint with the city of Minneapolis.

EXTRA: LETTER TO THE EDITOR BY ROBERT SAMPLES

“There was not any accountability,” said LaJune Lange, a retired district court judge.

In the late 1960s, Lange worked in the city’s Department of Civil Rights. Part of her job was investigating complaints against MPD officers, a job that she said came with tremendous power at the time.

“If we decided there was probable cause, we could have a hearing, a fact-finding hearing, and force the police officer through subpoena to come and testify,” Lange said.

But that changed in 1969 after Charles Stenvig, a Minneapolis police detective, was elected mayor.

Under Stenvig, police officers were no longer required to attend civil rights hearings, according to Lange.

“My position was abolished,” she said.

In his letter to the editor, Robert Samples wrote the department’s “powers had been stripped” by the city council.

The Samples family’s only option was to file a complaint with the Minnesota Department of Human Rights, setting off a fierce legal battle with the city that would go all the way to the state Supreme Court.

City of Minneapolis v Richardson

In March of 1974, the state found the officer’s actions and comments toward Randy Samples were motivated by bias because of his race.

Samuel Richardson, commissioner of the state Department of Human Rights, ordered the city of Minneapolis to apologize for the officers’ conduct, pay the Samples family $100 in damages and keep an official record of all complaints against police officers alleging racial discrimination.

The city instead appealed the ruling to the Minnesota Supreme Court, questioning the state’s authority to investigate the police department, arguing it overstepped.

Jerome Fitzgerald, the assistant city attorney at the time, told the Minneapolis Tribune the state “does not have the authority to tell a municipality how to operate its departments.”

But in 1976, the high court ruled the state did have the power to investigate public officials and institutions—like police departments—for discriminatory conduct.

The decision also stated, for the first time in Minnesota, that a police officer’s use of the N-word is a form of race-based discrimination.

“The use of the term “n*****” has no place in the civil treatment of a citizen by a public official,” wrote Justice Fallon Kelly in the majority opinion.

Kevin Lindsey, who served as commissioner of the Minnesota Department of Human Rights from 2011-2019, said the supreme court decision was significant.

“We were really just sort of at the beginning of what was discriminatory, what was inappropriate,” Lindsey said. “[The ruling] really established that the Department of Human Rights could take on significant issues for marginalized communities.”

Pattern and practice

Today, the state is still using that power to investigate Minneapolis Police for discriminatory policing.

Following the murder of George Floyd in May 2020, the state Human Rights Department announced it would launch an investigation to determine if MPD engages in a “pattern or practice” of race discrimination.

The final report, released in April, detailed historic racial disparities in policing. The agency said they found evidence that officers “consistently use racist, misogynistic, and disrespectful language” when interacting with the Black community.

The findings specifically note that some MPD officers and supervisors use the N-word to describe African Americans—the same word used to describe Randy Samples in 1971.

“I guess a lot of folks didn’t get the memo,” Carlson said, referencing the findings. “Here we are, this many years later, and not much has changed.”

“I think that we’ve taken a giant step nowhere.”

-Peggie Carlson

5 INVESTIGATES did not receive a response from current and former law enforcement officials in Minneapolis when asked to comment on the supreme court ruling and its impact on what’s happening today.

Spike Moss, a longtime Minneapolis resident, said he remembers seeing the photo of Randy Samples and believes nothing has changed.

“Here you are [in] 2022 and all of the ugly that was going on is still going on,” he said during an interview.

For the Samples sisters, the photo of their brother is a snapshot of the past, but also a warning of the problems and the debate that would resurface 50 years later.

“This with George Floyd wasn’t the beginning,” Carlson said. “It started a long time ago.”

Timeline from Samples to Floyd

April 10, 1971 — 12-year-old Randy Samples is arrested on Hennepin Avenue in downtown Minneapolis. The child was dragged down the street by two MPD officers, and claimed the officers used the N-word to describe him and other Black individuals in the crowd.

April 12, 1971 — The Minneapolis Tribune publishes a photo of an unidentified boy being pulled face down, by his ankles, by two Minneapolis Police officers.

April 23, 1971 — Samples family files a charge of racial discrimination with the Minnesota Department of Human Rights.

February 21, 1974 — The state finds the officers discriminated against Samples. The city appealed the finding.

January 23, 1976 — Minnesota Supreme Court rules that officers did discriminate against Samples because of his race and the use of the N-word is a form of race-based discrimination. The decision also confirmed the state’s power to investigate police departments for discriminatory conduct.

June 1, 2020 — Following the murder of George Floyd, the Minnesota Department of Human Rights opens an investigation into Minneapolis Police.

April 27, 2022 — The state finds there is probable cause that the city of Minneapolis and its police department engage in a pattern or practice of race discrimination.